|

Dossier Dossiers | ||||||||||||||||||

|

Billy Wilder, un regista tra due culture: dietro l'apparenza, sotto l'allusione (Prima parte) |

Billy Wilder, a director between two cultures: behind appearances, beneath allusions (Part 1) |

||||||||||||||||||

|

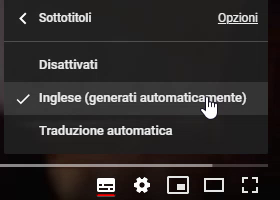

Note: - E' disponibile una versione pdf di questo Dossier. - Alcuni video di YouTube, segnalati dal simbolo |

Notes: - A pdf version of this Dossier is available. - Some YouTube videos, featuring the |

||||||||||||||||||

|

"Sono un miscuglio" Billy Wilder |

"I am a mélange" Billy Wilder |

||||||||||||||||||

|

1. Introduzione |

1. Introduction |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Quando la moglie è in vacanza/The seventh year itch (1955) |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

A qualcuno piace caldo/Some like it hot (1959) |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

La gonna di Marilyn sollevata dall'aria della grata della

metropolitana è diventata un'icona del XX secolo, e "Nessuno è

perfetto" una delle più famose e ricordate battute conclusive di un

film. Eppure, probabilmente molti di noi non saprebbero ricordare il

nome del regista di questi film - Billy Wilder. A differenza di

altri registi, il cui nome è estremamente popolare (Alfred

Hitchcock, Woody Allen, Stanley Kubrick ...), il nome di Billy

Wilder è quasi dimenticato, anche perchè, a differenza di molti suoi

colleghi, i suoi film non sono stati oggetto di moltissimi

contributi critici, e la bibliografia disponibile è relativamente

scarsa (Nota 1)(mentre abbondano i lavori biografici e le

interviste, tra cui quella fondamentale di Cameron Crowe - Nota 2).

Eppure, Wilder è stato autore, oltre che di commedie di grande

successo, di capolavori noir come La fiamma del peccato

(1945) e di drammi potenti come Viale del tramonto (1950), e la sua

carriera ha coperto cinquant'anni di cinema "classico"

hollywoodiano, fruttandogli, tra l'altro, dodici nominations

agli Oscar come sceneggiatore e otto nominations come

regista, sei Oscar effettivi, quattro suoi

film inclusi nell'elenco dei più grandi film americani stilata

dall'American Film Institute, e un numero di film considerati "degni

di conservazione" da parte del National Historic Register maggiore

di qualsiasi altro regista (Nota 3). In parte tutto ciò può essere spiegato con il disinteresse di Wilder, se non proprio disprezzo, per la visione del regista come "autore" (tipica di molti movimenti assimilabili alla Nouvelle Vague francese) e per la stessa attività dei critici cinematografici. Ciononostante, pur contestando e deridendo l'auto-referenzialità di "autori" come Godard, che secondo lui, con i loro virtuosismi stilistici, sembravano mettere in secondo piano l'importanza della trama e dello sviluppo psicologico dei personaggi, forse nessuno come Wilder può essere considerato come "autore" dei suoi film, visto che non ha mai diretto un film che non fosse stato scritto da lui - da cui l'importanza della sceneggiatura anche rispetto alla successiva realizzazione di un film. 2. Un regista tra due culture Pur essendo nato in una città della Galizia, oggi situata in Polonia ma allora parte dell'impero austro-ungarico, e portando dunque con sè il lascito del "vecchio mondo mittel-europeo", l'influenza americana fu sin dall'infanzia un elemento importante per Wilder (sua madre aveva vissuto in America da ragazza, un fratello maggiore era emigrato negli Stati Uniti). Proprio la sua conoscenza della cultura americana gli aprì le porte del giornalismo, portandolo presto a Berlino, dove ebbe modo di partecipare a pieno titolo all'atmosfera vivace della Repubblica di Weimar, un clima culturale fortemente influenzato da elementi come il jazz, il charleston, e in generale i film americani degli anni '20. Le esperienze come giornalista, riflesse poi in film come L'asso nella manica (1951) e Prima pagina (1974), saranno fondamentali per sviluppare quella tipica osservazione dei comportamenti umani e quel realismo di rappresentazione che sono una delle costanti dei suoi film. A Berlino Wilder iniziò a interessarsi di cinema e a collaborare a sceneggiature, finchè, all'ascesa di Hitler, nel 1934 decise di espatriare, prima a Parigi (dove girò il suo primo film, Mauvaise Graine o Amore che redime (1933), poi negli Stati Uniti (la madre, il patrigno e la nonna morirono ad Auschwitz). Questa sua condizione di "esule" condizionò sempre la visione della vita e del cinema di Wilder, anche se non gli fu difficile adattarsi alla cultura americana e, in particolare, al sistema produttivo hollywoodiano e all'allora imperante "star system". Come vedremo, se da una parte Wilder condivise pienamente i valori della sua nuova "patria di elezione", allo stesso tempo si sentì sempre un po' un "estraneo", il che gli permise di osservare e descrivere la società americana con un occhio distaccato - una posizione particolare, da eterno "esule", in bilico tra due culture molto diverse, che gli permise di vivere con intensità il confronto interculturale: il vedere cioè "il diverso come familiare, e il familiare come diverso". 3. Al crocevia di influenze diverse "Noi che avevamo le nostre radici nel passato europeo, penso, abbiamo portato con noi un atteggiamento nuovo nei confronti dell'America, un occhio nuovo con cui esaminare questo paese tramite il cinema, rispetto all'occhio dei cineasti nati in America, che erano abituati a tutto ciò che li circondava" - Billy Wilder (Nota 3) L'arrivo di Wilder negli Stati Uniti accadde in un momento particolare per la storia del cinema. Con la fine della stagione espressionista del cinema tedesco, che negli anni '20 era stato secondo solo a quello americano, e con l'avvento del nazismo, molti cineasti, sceneggiatori, tecnici e attori si era già trasferiti a Hollywood, e tra loro personalità come, tra gli altri, Peter Lorre, Marlene Dietrich, Ernst Lubitsch, F.W.Murnau, Emils Jannings, Conrad Veidt, Wilhelm Dieterle e Edgar G.Ulmer, che avrebbero profondamente influenzato il cinema americano degli anni a venire. I primi anni '30 avevano anche visto la definitiva affermazione del sonoro, che per Wilder, sceneggiatore prima ancora che regista, significava la possibilità di giocare moltissimo con dialoghi vivaci, sottintesi e allusioni e con la descrizione di situazioni e personaggi che non sarebbero stati possibili con gli "intertitoli" inseriti nei film muti per chiarire la trama e i contenuti delle conversazioni. E proprio Ernst Lubitsch, maestro delle commedie romantiche dall'eleganza formale, dai dialoghi frizzanti e dalle raffinate allusioni sessuali (tanto da aver dato origine al cosiddetto "tocco di Lubitsch"), sarebbe stato, insieme a Erich von Stroheim, uno dei maggiori ispiratori di Wilder che non a caso dichiarò più volte che quando non sapeva come delineare una situazione, si chiedeva sempre: "Come avrebbe fatto Lubitsch?". Wilder si inserì agevolmente nel sistema produttivo hollywoodiano, allora al suo apogeo, e entro i cui limiti e col cui supporto produsse il meglio del suo lavoro, rendendosi però man mano sempre più indipendente ma al contempo scegliendosi con cura i collaboratori, in primo luogo i suoi cosceneggiatori di una vita, Charles Brackett (con cui scrisse tredici film) e più tardi I.A.L.Diamond (con cui ne scrisse undici). Paradossalmente, poi, Wilder operò principalmente nel periodo in cui fu in vigore lo stretto codice censorio detto Production Code (o Hays Code, dal nome del presidente della Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America), con cui, dal 1934 al 1968, gli studios si auto-imposero limiti severissimi nella rappresentazione dei contenuti dei film, in particolare riguardo al sesso e alla violenza. Proprio l'impossibilità di "mostrare" direttamente ed esplicitamente, impose (e consentì) a registi come Wilder di dare sfogo alla propria inventiva e creatività, giocando moltissimo, come vedremo, sui sottintesi, sui doppi sensi, sulle allusioni. Ma la particolarità della figura di Billy Wilder consiste anche nel fatto che, pur lavorando entro i confini del sistema hollywoodiano, da "esule", "emigrato" e "osservatore esterno" poteva usare la sua sensibilità europea per cogliere, meglio di molti altri americani, le ansie, le frustrazioni e le ossessioni di una società verso la quale continuò per tutta la vita a provare un senso di non-appartenenza e di estraneità: di qui la "doppia prospettiva" con cui riusciva a considerare questa società, e le diverse, e a volte, contrastanti, sensibilità che lo portarono a creare un cinema "di mezzo", quasi da intermediario tra due culture: "Anche se i film di Wilder si situano sempre nella corrente tradizionale del cinema di intrattenimento hollywoodiano, ciò che li rende speciali e audaci è una forma di critica sociale che lavora entro, e tuttavia fa pressione contro, il sistema degli studios, con la costante minaccia di diventare più cupo, più inquietante, più sessuale e più politico di quanto permetta il sistema stesso" (Nota 4). 4. Fra travestimento e mascheramento "Qualsiasi significato vogliate trovare nei miei film, è tutto messo come di contrabbando, sapete - come introdotto di frodo" - Billy Wilder (Nota 5, p. 68) Al livello più diretto ed esplicito, l'interesse di Wilder per il conflitto tra l'essere e l'apparire, tra la persona e la personificazione, tra la realtà e la finzione, tra l'autenticità e l'inganno, si esprime con il tema del travestimento e del mascheramento, che appare spesso nei suoi film, a prescindere dal genere a cui appartengono, ed è strettamente legato alla sua condizione di "esule": "La propensione di Wilder per la finzione e per lo "spacciarsi per un altro" deve anche essere vista nei termini della sua esperienza di esulee. La perdita della sicurezza politica ed economica e dell'identità sociale e personale costituisce una parte fondamentale dell'essere un rifugiato, e le strategie di impersonare qualcun altro, di travestirsi, di "cambiare forma", e di "mimetizzarsi" culturalmente sono centrali negli sforzi dell'esule di sopravvivere al trasferimento forzato, alle difficoltà economiche, e all'ostracismo sociale ... Così che anche quando sono al servizio dell'intrattenimento, lo "spacciarsi per un altro" e il mascheramento comportano sempre una dimensione politica" (Nota 4, p. 118-119) Già nel titolo originale del suo primo da regista, The Major and the Minor - Frutto proibito), cela un'ambiguità, in quanto Maggiore e Minore stanno anche per i due protagonisti del film, un maggiore dell'esercito (Ray Milland) e una ragazza (Ginger Rogers) che, per pagare la tariffa ridotta sul treno, si finge minorenne, più esattamente dodicenne. Questo provoca una serie di situazioni comiche ma anche imbarazzanti, poichè il maggiore si innamora presto della ragazza, ma non può ovviamente accettarlo ... Il mascheramento viene tenuto sul filo del rasoio per quasi tutto il film, e la ragazzina finisce addirittura per passare la notte nel compartimento-letto del maggiore, che le leggerà la fiaba della buonanotte (come vedremo, la scena degli incontri notturni su un treno comparirà anche in altri film di Wilder). Dietro un meccanismo di commedia leggera si nasconde così il tabù del desiderio sessuale per una minorenne (oggi diremmo pedofilia). |

A breeze from the subway passing below lifts Marilyn's skirt:

this image has become a 20th century icon, and "Nobody's perfect"

one of the best-known final punchlines of a movie. And yet, probably

most of us would not be able to remember the name of the director of

these films - Billy Wilder. Unlike other directors, whose name is

extremely popular (Alfred Hitchcock, Woody Allen, Stanley Kubrick

...), Billy Wilder's name is almost forgotten, also because , unlike

many of his colleagues, his films have not received a great deal of

critical attention, and the available bibliography is relatively

scarce (Note 1)(while there are several biographical works as well

as interviews, among which Cameron Crowe's basic one - Note 2). And

yet, Billy Wilder has authored enormously popular comedies, noir

masterpieces like Double indemnity (1945) and powerful

dramas like Sunset Boulevard (1950), and his career has

spanned fifty years of "classical" Hollywood cinema, bringing him

twelve Academy Award nominations as screenwriter and eight

nominations as director, six actual Academy Awards, four of his

films included in the list of the greatest American movies created

by the American Film Institute, and a number of movies considered as

"worthy of preservation" by the National Historic Register greater

than any other director (Note 3). All this can partly be explained by Wilder's indifference, if not open contempt, for a vision of the director as "auteur" (which was typical of several film movements associated with the French Nouvelle Vague) and for the very work of movie critics. Despite this, and while contesting and even mocking the self-centredness of "auteurs" like Godard, who (he thought) with their stylistic virtuosity seemed to leave the importance of the plot and the psychological development of characters in the background, maybe no director like Wilder can be considered as the "author" of his movies, considering that he never directed a movie which he had not written - and this also accounts for the relative greater importance of the script than the actual shooting of the film. 2. A director between two cultures Despite being born in a town in Galicia, now in Poland but then part of the Austro-Hungarian empire, thus bringing with him the legacy of the "old mittel-european world", the American influence was an important factor for Wilder since his childhood (hi mother had lived in the USA as a girl, an elder brother had emigrated to the States). It was his knowledge of American culture that opened the way to journalism, taking him soon to Berlin, where he could fully share the lively, if not frantic, atmosphere of the Weimar Republic: a cultural climate which was strongly influenced by such features as jazz, charleston, and, more generally, the American movies of the '20s. Wilder's experience as a journalist, which would later be reflected in such movies as The big carnival - Ace in the hole (1951) and The front page (1974), would be crucial for developing his typical ability to observe human behaviour and his realistic portrayal of situations which are a constant feature of his movies. In Berlin Wilder started getting involved with cinema and collaborating on scriptwriting, until, with Hitler's advent, in 1934 he decided to move, first to Paris (where he shot his first movie, Mauvaise Graine (1933), then to the USA (his mother, stepfather and grandmother all died in Auschwitz). His condition as an "exile" always affected his vision of life and of cinema in particular, although he did not find it difficult to adapt to American culture, and especially to the Hollywood production system and to the then prevailing "star system". As we shall see, if on the one hand Wilder fully shared his new country's values, on the other hand he always felt as an "outsider", which allowed him to observe and describe American society with a detached eye - a peculiar position, a never-ending "exile's" condition, hovering between two very different cultures, which allowed him to live to the full the intercultural confrontation: seeing "the different as familiar, and the familiar as different". 3. At the crossroads of different influences “We who had our roots in the European past, I think, brought with us a fresh attitude towards America, a new eye with which to examine this country on film, as opposed to the eye of native-born movie makers who were accustomed to everything around them” - Billy Wilder (Note 3) Wilder's arrival in the USA happened at a particular time in the history of cinema. With the end of the expressionist seaszon of German cinema, which in the '20s had been second only to American cinema, and with the advent of Nazism, many moviemakers, scriptwriters, technicians and actors had already moved to Hollywood, among whom celebrities like Peter Lorre, Marlene Dietrich, Ernst Lubitsch, F.W.Murnau, Emil Jannings, Conrad Veidt, Wilhelm Dieterle and Edgar G.Ulmer, who would deeply affect American cinema in the following years. The early '30s had also seen the final exploit of sound films, which for Wilder (then a scriptwriter rather than a director) meant the opportunity to play extensively with witty dialogues, understatements and allusions and with the description of situations and characters, all of which would not have been possible by using the "intertitles", which in silent movies were inserted so as to clarify the plot and the content of dialogues for the audience. Ernst Lubitsch, the master of romantic comedies featuring formal elegance, pungent dialogues and refined sexual allusions (what was later called "the Lubitsch touch") would be, together with Erich von Stroheim, one of the most influential figures in Wilder's career - he often declared that when he did not know how to stage a situation, he would ask himself, "How would Lubitsch do it?". Wilder easily entered the Hollywood production system, then in its highlight, and within the limits, but also with the support, of such a system, he produced the best of his work, making himself more and more independent but at the same time carefully choosing his collaborators, first of all his co-screenwriters, Charles Brackett (who wrote thirteen movies with him) and later I.A.L.Diamond (his favourite partner in eleven movies). Paradoxically, Wilder worked mainly during the time when the censorship code known as Production Code (or Hays Code, Hays being the name of the president of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America) was strictly enforced. Through this code (which was enforced from 1934 to 1968) Hollywood studios self-imposed very strict limits to what could be shown in movies, especially in the realms of violence and sexuality. This prohibition to "show" things directly and explicitly obliged (but at the same time allowed) directors like Wilder to express their creativity, by playing around, as we shall see, with understatements, double entendre, and allusions. However, the peculiarity of Wilder's work is also due to the fact that, despite working within the limits of the Hollywood system, as an "exile", "expatriate" and "outsider" he could use his European sensibility to describe, better than many other American directors, the anxieties, frustrations and obsessions of a society which throughout his life he accepted with a sense of non-belonging and "foreignness" - this was the source of his "double perspective", through which he was able to consider this society with differing, and sometimes contrasting, sensibilities. And this was what led him to create a "middle" cinema, almost an intermediary between two cultures: "While Wilder’s films are always positioned in the mainstream of Hollywood entertainment cinema, what makes them special and audacious is a form of social criticism that works within, and yet pressures against, the studio system, always threatening to become darker, more disturbing, more sexual, and more political than the system allows" (Note 4) 4. Between cross-dressing and masquerading “Whatever meaning you will find in my pictures, it’s all put in kind of contraband, you know - sort of smuggled in.” - Billy Wilder (Note 5, p. 68) At a more direct and explicit level, Wilder's interest for the conflict between being and appearing, between the real person and its embodiment, between reality and fiction, and between authenticity and deceit, is often expressed through cross-dressing and masquerading - themes which often appear in his movies, no matter which "genres" they seem to belong to, and is strictly linked to his condition as an "exile": "Wilder’s penchant for masquerade and impersonation has also to be seen in terms of his experience of exile. The loss of political and economic security and of social and personal identity is a fundamental part of being a refugee, and strategies of impersonation, drag, shape shifting, and cultural mimicry are central to the exile’s efforts to survive forced displacement, economic hardship, and social ostracism ... Thus even when in the service of entertainment, impersonation and masquerade always entail a political dimension" (Note 4, p. 118-119) Starting from the title of his American début film as a director, The Major and the Minor, ambiguity is a central theme, since Major and Minor are also the two main characters, an army major (Ray Milland) and a girl (Ginger Rogers), who, in order to buy a reduced fare train ticket, pretends to be a minor, a twelve-year-old girl. This causes a series of comic but also embarrassing situations, since the major soon falls in love with the girl, a fact which he obviously cannot accept ... This masquerade is kept "on a tightrope" for most of the movie, and the "girl" ends up spending the night in the major's compartment - he will even read a fairy tale to her (as we shall see, this scene of night encounters aboard a train will appear in other Wilder movies). Behind a façade of light comedy lurks the taboo of sexual desire for a minor (which today we would call paedophilia). |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Frutto proibito/The Major and the Minor (1942) |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Anche nel suo secondo film,

I cinque segreti del

deserto, ambientato in Egitto durante la seconda guerra

mondiale, non manca il mascheramento: un soldato inglese (Franchot

Tone) si finge cameriere in un albergo per infiltrarsi nello stato

maggiore di Rommel e scoprire dove i tedeschi hanno nascosto dei

depositi di approvvigionamenti, dando origine ad un'alternanza di

commedia e suspense in quello che è sostanzialmente un film di

guerra. Da notare che, per impersonare Rommel, Wilder chiamò il

regista Erich von Stroheim (che apparirà anche nel successivo

Viale del tramonto), che era stato tra i primi ad

auto-esiliarsi in America all'avvicinarsi del nazismo. Persino in un film ambientato in un campo di prigionia nazista, Stalag 17 (trailer italiano qui), Wilder riesce ad aggiungere tocchi di commedia e quindi a mischiare i generi (cosa per cui il film fu aspramente criticato all'uscita). Nelle baracche in cui sono confinati, i prigionieri americani progettano una fuga, ma sospettano che uno di loro (William Holden) sia una spia, visto che intrattiene piccoli affari con i tedeschi. Pur nella loro tragica situazione, i prigionieri non rinunciano ad organizzare una festa e a ballare tra di loro, e qualcuno si traveste persino da donna (video in basso a sinistra). E si inventano pure una scena di "indottrinamento" (video in basso a destra), con uno di loro che, atteggiandosi a Hitler, fa loro una predica: e quando il comandante del campo interviene per sedare questa messinscena, i prigionieri (che finora abbiamo visto solo di spalle), improvvisamente si voltano ... e scopriamo che sono tutti truccati da Hitler! Al che il comandante (interpretato, guarda caso, dal regista Otto Preminger, anche lui esule tedesco in America) sbotta, "Un solo Hitler è abbastanza!". |

In his second film (Five graves to Cairo),

too, set in Egypt during the War War II, we return to masquerade: an

English soldier (Franchot Tone) pretends to be a waiter in a hotel

in order to get access to Rommel's General Staff and discover where

the Germans have buried some war supplies - thus mixing comedy and

suspense in what is basically a war movie. Note that to play

Rommel's role Wilder called Erich von Stroheim (later to appear in

Sunset Boulevard too), who had been one of the first directors to

choose to expatriate to America at the advent of Nazism. Even in a movie set in a Nazi prisoner-of-war camp, Stalag 17 (watch the full film here), Wilder manages to introduce touches of comedy, thus mixing the genres (which was harshly criticized when first screened). In the prisoners' barracks, the soldiers plan to escape, but suspect that one of them (William Holden) may be a spy, given that he does some small business with the Germans. Even in their tragic situation, the prisoners manage to organize a party and start dancing, and some of them even cross-dress as women (video below left). And they also stage a session of "indoctrination" (video below right), with one of them who, posing as Hitler, lectures to the others: and when the commanding officer of the camp orders them to stop this masquerade, the prisoners (whom we have so far seen only from behind), suddenly turn ... and we discover that they are all camouflaged as Hitler! Which prompts the commander (a role played by the director Otto Preminger, a German exile in America) to blurt out, "One Hitler is enough!". |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Stalag 17 (1953)

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

A qualcuno piace caldo/Some like it hot (1959) |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Il travestimento qui genera ben più di un malinteso superficiale, ma

arriva a toccare i temi ben più profondi dell'identità sessuale e di

genere e a mettere in discussione le false sicurezze e le ipocrisie

di una società. Mentre infatti Curtis si traveste (ancora!) da

miliardario per sedurre Marilyn, Lemmon è costretto a subire le

avances di un vero vecchio miliardario, con cui dovrà ballare

il tango tutta la notte. E al ritorno nella loro camera d'albergo

(video in basso a sinistra), Curtis trova Lemmon esaltato perchè si

è appena ... fidanzato col miliardario! E alla rimostranza di Curtis, "Ma

tu sei un uomo, perchè un uomo vorrebbe sposare un altro uomo?",

candidamente Lemmon risponde, "Per sistemarsi!". E Curtis ribatte,

"Ma ci sono le leggi, le convenzioni, sono cose che non si

fanno! ... Ripeti a te stesso: Sono un uomo, sono un uomo!".

Qui siamo ben al di là dello scambio di ruoli e della mascherata per

burla: ciò che viene messo in gioco è l'essenza stessa della propria

identità sessuale ... ma il conflitto tra "essere" e "apparire" non

viene mai risolto nel film, visto che, come abbiamo visto nel video

di apertura di questo Dossier, Lemmon non riuscirà ad

uscire dal suo nuovo ruolo sociale di donna, e il suo spasimante

accetterà tutto con quella famosissima battuta finale, "Nessuno è

perfetto!". |

Cross-dressing generates much more than a superficial misunderstanding in this movie, but manages to deal with deeper implications, including sexual and gender identity and questioning the false values and hypocrisy of a whole society. As Curtis dresses up (once again!) as a millionaire to seduce Marilyn, Lemmon is obliged to suffer the advances of a real old millionaire, with whom he ends up dancing the tango all night long. And when they return to their room (video below left), Curtis finds Lemmon all excited because he has just ... got engaged with the millionaire! And when Curtis remarks, "But you're a man, why should a man want to marry another man?", Lemmon innocently replies, "To settle down!". And Curtis retorts, "But there are laws, conventions, these are things that can't be done! ... Repeat to yourself: I'm a man, I'm a man!". Here we go well beyond role reversal and masquerading for fun: what is at stake is the essence of one's own sexual identity ... but the conflict between "being" and "appearing" is never solved in the movie, given that, as we saw in the opening video of this Dossier, Lemmon will not be able to escape from his new social role as a woman, and his suitor will accept anything from him, up to the final punch line, "Nobody's'perfect!". | ||||||||||||||||||

|

A qualcuno piace caldo/Some like it hot (1959)

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Irma la dolce/Irma la douce (1963) |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Il gendarme finisce per innamorarsi della dolce Irma, e a questo

punto non solo le sue iniziali certezze oscillano, ma, nel tentativo

di assicurarsi i suoi servigi "in esclusiva" (ed anche, in realtà,

per convincerla a ricambiare i suoi sentimenti), arriverà a

travestirsi da gentiluomo inglese, Lord X (sequenza qui sotto).

Ancora una volta, il mondo di Wilder è governato dai ruoli che la

società ci impone, e gli individui devono ricorrere a tutta una

serie di sotterfugi (inganni, mascheramenti, equivoci e finzioni di

ogni tipo) per far emergere, e alla fine trionfare, i sentimenti

veri e gli autentici rapporti tra le persone, in un film che è al

contempo una commedia assolutamente classica e un dramma personale e

sociale. "All'inizio degli anni sessanta, [Wilder] anticipa la

crisi del cinema hollywoodiano (di cui è uno degli indiscussi

maestri), ipotizzando quella pratica di contaminazione dei generi

che qui ancora non si vede, ma che si può intuire come sbocco

inevitabile" (Nota 7). |

The policeman ends up falling in love with the sweet Irma, and at this point not only do his initial certainties seem to waver, but, trying to ensure her "services" exclusively for him (while also trying to persuade her to return his feelings), he will decide to dress up as an English gentleman, Lord X (video below). Once again, Wilder's world is dominated by the roles that society imposes on us, and people have to adopt all kinds of deception (deceit, masquerade, ambiguities and make-believe) in order to make explicit true feelings and authentic relationships. This movie is both a truly "classical" comedy and a personal and social drama. "At the start of the '70s [Wilder] anticipates the crisis of Hollywood cinema (of which he is certainly one of the masters), introducing that particular genre contamination which is not yet explicit here, but can be perceived as its ultimate result" (Note 7). | ||||||||||||||||||

|

Irma la dolce/Irma la douce (1963) |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

In uno dei suoi ultimi film, Che cosa è successo tra mio mio

padre e tua madre? (il titolo originale, Avanti!, fa

riferimento alla parola italiana che i protagonisti usano per

rispondere a chi bussa alla porta della loro camera d'albergo),

Wilder torna a descrivere la trasformazione di una persona,

questa volta in modo più interiorizzato e forse più profondo. Un

ricco uomo d'affari americano, Wendell Armbruster III (Jack Lemmon)

arriva ad Ischia per recuperare la salma del padre e scopre che è

morto proprio tra le braccia di un'amante, che vedeva una volta

all'anno durante le sue vacanze in Italia. Ad Ischia incontra però

anche la figlia dell'amante del padre, la londinese Pamela Piggott

(Juliet Mills), anche lei ignara di quanto accaduto. Le reazioni dei

"figli" sono molto diverse: all'iniziale giudizio morale assoluto di

Armbruster fa riscontro la flessibilità e la comprensione umana di

Pamela, finchè questa occasione di incontro finirà per insegnare a

Armbruster a godersi di più la vita e a prenderla con più calma e

serenità. |

In one of his last movies, Avanti! (the title refers

to the Italian expression that the characters use to invite people

knocking at the door of their hotel room to come in), Wilder once

again describes the transformation of a person, this time probing

deeper into his personality. A rich American businessman, Wendell

Armbruster III (Jack Lemmon) arrives in Ischia, Italy to arrange the

funeral of his father and discovers that he died while staying with

his lover, whom he used to meet in Italy once a year, during his

usual Italian holiday. In Ischia, however, he meets the daughter of

his father's lover, the London lady Pamela Piggott (Juliet Mills),

who is unaware, as he is, of what happened. The "children"'

reactions are very different: while Armbruster initially shows a

rigid moral judgment, Pamela is much more flexible and full of human

understanding ... they will gradually get to know each other better,

and this will teach Armbruster to enjoy life in a less frantic way. |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Che cosa è successo tra mio padre e tua madre?/Avanti! (1972) |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

"Per dipingere il crescente amore tra Armbruster e Pamela,

Wilder usa uno dei suoi meccanismi preferiti - la trasformazione -

ma come mezzo per rendere più umani i personaggi, non per

mascherarli. Armbruster comincia ad indossare la giacca di suo

padre; Pamela, il vestito di sua madre. Poi cominciano ad usare gli

stessi soprannomi che i loro genitori usavano l'uno con l'altra -

Willie e e Kate. Che cosa è successo tra mio padre e tua madre? è

l'unico film di Wilder in cui ci si aspetta che un atto di

sotterfugio duri per tutta una vita perchè è fondato sull'amore"

(Nota 6, p. 97-98). Certo, le convenzioni sociali non vengono

cancellate: anche Armbruster e Pamela decideranno di ritrovarsi, come i

facevano i loro genitori, una volta all'anno ad Ischia, pagando con

undici mesi di "vita borghese normale" quell'unico mese in cui

saranno veramente se stessi. Anche in questo caso, come in Irma la dolce, la commedia assume toni, se non drammatici, di seria riflessione, su vari fronti: il moralismo manicheo con cui gli americani guardano all'Europa, e in particolare all'Italia, messo a confronto con l'umanità ed anche il senso di godimento della vita del vecchio continente; l'adulterio come modo di recuperare il valore del tempo che scorre ed un rapporto più umano con le persone e le cose; l'ironia e la satira, tra tenerezza e cinismo, con cui Wilder guarda a molte sfaccettature della società americana. Certamente i tempi sono cambiati; con l'abolizione del codice censorio, che fino a pochi anni prima aveva causato le aspre polemiche di Baciami, stupido, Wilder è ora in grado di affrontare più apertamente, e soprattutto con maggiore serenità, temi considerati prima scottanti: "Dopo anni di elusione della censura con doppi e tripli sensi, questo è il primo film di Wilder a contenere spunti irriverenti e addirittura qualche scena di nudo. Tutto molto sfumato e mai gratuito, ma è un po' come sentire papà dire parolacce per la prima volta" (Nota 2, p. 351). Fine della Prima parte. Vai alla Seconda parte |

"To portray the growing love between Armbruster and Pamela, Wilder

uses one of his favourite devices - transformation - but as a

means of humanizing the characters, not of disguising them.

Armbruster starts wearing his father's coat; Pamela, her mother's

dress. Then they start using the same nicknames their parents had

for each other - Willie and Kate. Interestingly, Avanti! is

Wilder's only film in which an act of deception is expected to last

a lifetime because it is founded on love" (Note 6, p. 97-98).

Social conventions are not really cancelled: Armbruster and Pamela

will decide to meet, as their parents did, in Ischia once a year,

paying with eleven months of a "normal bourgeois life" that other

month when they will live their real selves. In this case, too, as in Irma la Douce, the comedy takes on tones which, if not truly dramatic, stimulate a serious reflection at different levels: the Manichean moralism theough which Americans look at Europe, and Italy in particular, compared with the sense of humanity and enjoyment of life of the old continent; adultery as a way to catch up with the value of passing time and a more humane relationship with people and things; the irony and satire, tinged with both tenderness and cynicism, through which Wilder looks at several aspects of American society. Certainly, times have changed: after the abolition of the Hays Code, which only a few years earlier had caused the harsch reactions to Kiss me, stupid!, Wilder can now deal more explicitly with hot subjects: "After so many years in which he bypassed censorship through double (and triple!) entendres, this is the first of Wilder's movies to display disrespectful touches and even some nudity. Everything is toned-down and never gratuitous, but it's a bit like hearing daddy use swearwords" (Note 2, p. 351). End of Part 1. Go to Part 2 |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Per

saperne di più ... * Dal sito cinekolossal.com: - Billy Wilder: cenni biografici, filmografia, premi, collegamenti * Dal sito wikipedia.org: - Billy Wilder - Billy Wilder - Nessuno per 15 anni dalla morte del regista * Video dal sito ovovideo.com: - Billy Wilder * Dal canale YouTube di Emanuele Rauco: - Chiedi chi era Billy Wilder |

|

Want to know more? * From The Independent website: - Billy Wilder and his best movies by Graeme Ross * From the Encyclopaedia Britannica website: - Billy Wilder * From the Senses of Cinema website: - Billy Wilder - filmography, bibliography, articles, web resources * From the Reel Classics website: - Billy Wilder - with many further links * From the indiewire.com website: - The films of Billy wilder: A retrospective by Oliver Lyttelton * From the FilMagicians - Portrait of a 60% Perfect Man: Billy Wilder interview (1982) * From Kevin Kavanagh's YouTube channel: - Billy Wilder: His 20 Greatest Films * From the Writers Guild Foundation YouTube channel: - The writer speaks: Billy Wilder * From the midnighttiptoes YouTube channel: - Jack Lemmon on Billy Wilder * From the Eyes On Cinema YouTube channel: - Billy Wilder talks about filmmaking (audio interview, 1978) * From adam20xx You Tube channel: - Nobody's perfect" - The making of "some like it hot" with Monroe, Curtis and Lemmon - TV documentary * From the Hillsdale YouTube channel: - Leonard Maltin: The legacy of Billy Wilder * From Gill R. Godfrey's YouTube channel: Billy Wilder Tapes - "Billy, how did you do it?", in conversation with Volker Schloendorff: - Tape 1 - Tape 2 - Tape 3 |