Dossiers

|

Dossier Dossiers |

| Pedro (Terza parte) |

Pedro Almodóvar: identity issues (Part 3) |

|

Note: - E' disponibile una versione pdf di questo Dossier. - Alcuni video di YouTube, segnalati dal simbolo -- Il simbolo 10. Ritorni e ricordi |

Notes: - A pdf version of this Dossier is available. - Some YouTube videos, featuring the - The symbol 10. Returns and recollections |

| Tutti i film di Almodóvar hanno nostalgia dell'era di Franco, ma la storia di solito ritorna come immagine grottesca piuttosto che come un passato glorioso. (Nota 1) | All Almodóvar movies are nostalgic of the Franco era, but history usually comes back as grotesque image rather than a glorious past. (Note 1) |

|

La mala educación si svolge in tre momenti distinti, tutti nel passato: l'azione ha iniszio nel 1980 - un anno importante per (Il trailer del film è visibile nel video 1 qui sotto; il film completo è disponibile su YouTube in spagnolo con sottotitoli generati automaticamente [video 2 qui sotto]. Il minutaggio che compare nella seguente descrizione della trama fa riferimento a questo video) Nel 1980 a Madrid, dunque, un regista gay, Enrique (Fele Martinez), alla ricerca di soggetti per il suo prossimo film, riceve la visita di un giovane (Gael Garcia Bernal)(0:02:39), che si presenta come Ignacio, un amico d'infanzia, suo compagno nel collegio cattolico frequentato da entrambi, e che era stato il primo amore di Enrique. Enrique ha difficoltà a riconoscerlo dopo tanti anni, ma il giovane, che ora fa l'attore e vuole farsi chiamare Angel, gli propone una sceneggiatura, "La visita", con l'intento di esserne l'interprete. Enrique comincia a leggere la storia e allo stesso tempo la visualizza nella sua mente come un film, narrato dalla voce di Ignacio (0:07:22): siamo ora nel 1977, a Valencia, dove Ignacio si esibisce come travestito sotto il nome di Zahara, doppiando in playback le canzoni di una famosa cantante spagnola degli anni '50 e '60, Sara Montiel (0:09:26). Il mattino dopo, sempre travestito da Zahara, Ignacio si presenta da Padre Manolo (Daniel Giménez Cacho)(0:23:49), da cui era stato sedotto da ragazzo, e che aveva espulso dal collegio, per gelosia, Enrique. Ignacio ora consegna al prete una copia di questa storia, minacciando di rivelare tutto se non riceverà un milione di pesetas. (Vediamo alcuni flashback, ambientati nel 1964: 0:25:34 -0:43:08). Torniamo al 1980 (0:43:08). Angel insiste per recitare la parte di Zahara nel film, ma Enrique non è convinto e i due litigano. Turbato e incuriosito, Enrique si reca nel villaggio della Galizia dove era nato Ignacio (0:56:35) per parlare con la madre, scoprendo che Ignacio in realtà è morto da anni e che il giovane attore è in realtà il fratello minore di Ignacio, Juan. Al ritorno a Madrid, Angel si ripresenta (1:02:13), visibilmente dimagrito, e questa volta Enrique, senza menzionare la sua scoperta, gli affida la parte - e i due nel frattempo diventano amanti. Mentre filmano la scena finale (1:04:55), compare sul set un certo Signor Berenguer (Lluis Homar), un uomo d'affari che si rivela essere in realtà Padre Manolo, in cerca di Juan. Berenguer racconta ad Enrique la sua versione della storia: nel 1977 il vero Ignacio, ora un travestito in procinto di cambiare sesso, lo aveva ricattato minacciando di rivelare la pedofilia del prete. Berenguer aveva così fatto la conoscenza di Juan, che si era prestato a favori sessuali in cambio di denaro. Nel frattempo, le minacce di Ignacio avevano portato Berenguer/Padre Manolo ad ucciderlo - tramite una dose fatale di eroina somministratagli da Juan. A questo punto, Enrique scaccia dal set Juan, chiudendo il suo rapporto con lui (1:32:38). La descrizione dettagliata della trama di La mala educación è stata necessaria per capire la complessa struttura narrativa del film, che si basa su tre "visite" (da cui il nome della sceneggiatura di Ignacio/Juan) ma che si svolge non in modo lineare, ma con frequenti salti nel tempo, tra il presente (1980), il passato della sceneggiatura (1977) e il lontano passato dell'infanzia dei ragazzi nella scuola religiosa (1964); inoltre, gli eventi sono visti e narrati dai vari personaggi, contribuendo a presentare ed intersecare prospettive e punti di vista diversi - ma "quella complessità qui obbedisce ad un suo ordine e ... l'implausibilità ... non comporta un caos narrativo" (Nota 2), nemmeno per lo spettatore. Congruenti con questa struttura "di film nel film" (o, se si vuole, "di scatole cinesi") sono i titoli iniziali (0:00:06), che accostano con violenza testi e immagini con uno stile visivo chiaramente ispirato ai famosi titoli che Saul Bass aveva creato per Hitchcock (come in La donna che visse due volte, USA 1958), nonchè alle celeberrime colonne sonore composte da Bernard Herrmann per lo stesso Hitchcock. Questi rimandi visivi e sonori non sono fini a se stessi, ma sottolineano la volontà di Insieme al tema della "storia" e del "narrare" (Enrique è un regista, Ignacio/Juan scrivono racconti e sceneggiature, e tutti raccontano la loro versione degli eventi), e che abbiamo visto apparire in molti film di Quasi a sottolineare il sottotesto storico e politico di La mala educación, il film, dopo aver inaugurato (primo film spagnolo) il Festival di Cannes, doveva uscire in Spagna due giorni dopo le elezioni generali. Tre giorni prima di queste elezioni, l'11 marzo 2004, ci furono alcuni terribili attentati in stazioni ferroviarie di Madrid, che provocarono 191 morti. Il governo conservatore di Aznar accusò di ciò il movimento separatista basco ETA (mentre poi si riverò essere opera di Al-Qaeda in risposta al sostegno fornito da Aznar all'invasione dell'Iraq da parte dell'America di Bush). Si parlò di rimandare le elezioni, e |

La mala educación involves three time levels, all of them in the past: the movie starts in 1980 - an important year for Almodóvar, the one which marked his first feature film, (See the film trailer in video 1 below; the comple movie is available on YouTube in Spanish, with automatically-generated subtitles [video 2 below]. The time references (e.g. 00:02) which appear in the following description of the plot refer to this video). Madrid, 1980. A gay film director, Enrique (Fele Martinez), in search for topics for his next movie, meets a young man (Gale Garcia Bernal)(0:02:39), who introduces himself as Ignacio, a childhood friend and schoolmate in the Catholic school attended by both - and also Enrique's first love. Enrique can hardly recognize him after all these years, but Ignacio, who is now an actor and wants to be called Angel, gives his a film script, "The visit", wishing to play the leading role in the possible movie. Enrique starts reading the script, visualizing it at the same time as a movie, narrated by Ignacio's voice (0:07:22): we are now in 1977, in Valencia, where Ignacio performs as a transvestite under the name of Zahara, singing in playback the songs of a famous Spanish singer of the '50s and '60s, Sara Montiel (0:09:26). The next morning, dressed as Zahara, Ignacio goes to visit Father Manolo (Daniel Giménez Cacho)(0:23:49), who had seduced him as a child and, out of jealousy, had also expelled Enrique from the school. Ignacio now gives teh priest a copy of this story, threatening to reveal everything unless he is paid a million pesetas (We see some flashbacks, set in 1964: 0:25:34 - 0:43:08). Back to 1980 (0:43:08). Angel insists on playing Zahara's role in the movie, but Enrique disagrees and they quarrel. Enrique is disturbed and goes to the village in Galicia where Ignacio was born (0:56:35) and meets his mother - only to learn that Ignacio has been dead for a few years and the young actor (Angel) is actually Ignacio's younger brother Juan. Back in Madrid, Angel calls on Enrique again (1:02:13), having clearly lost weight, and this time Enrique, without disclosing what he has discovered, agrees to let him have the role in the movie - and in the meantime they become lovers. While they are shooting the final scene (1:04:55), a certain Senor Berenguer (Lluis Homar) appears on the set - he introduces himself as a businessman but is in reality Father Manolo, looking for Juan It was worth giving a detailed description of the plot of La mala educación to realize the complex narrative structure of the movie, which is based on three "visits" (as the title of Ignacio/Juan's screenplay suggests) but is not treated in a linear way, with frequent "time jumps" between the present (1980), the past of the screenplay (1977) and the farther past of the boys' childhood in the religious school (1964); besides, events are seen and told by the various characters, thus contributing to present and intertwine different perspectives and points of view - These visual and musical references are not an end in themselves, but underscore Together with the theme of "story" and "narration" (Enrique is a film director, Ignacio/Juan write stories and screenplays, and all of them tell their own versions of the events), which regularly appears in several of Almost to underscore the historical and political subtext of La mala educación,the movie, after opening (first Spanish film in history) the Cannes Film Festival, was supposed to be released in Spain after the general elections. Three days before these elections, on March 11th, 2004, there were some terrorist attacks in Madrid railway stations, with 191 victims. Aznar's conservative government blamed the ETA basque separatist movement for this (while it was later confirmed to be Al-Qaeda's response to Aznar's formal support of Bush's invasion of Iraq). There were plans to put off the elections, and |

Video 1 Video 2

La mala educación - Bad education (2004)

| Il successivo

film di Il film si apre con la veduta di un cimitero di un villaggio di campagna, spazzato dal vento, in cui molte donne sono al lavoro per pulire le tombe di famiglia (e una di esse, Agustina (Blanca Portillo) si occupa della sua stessa tomba acquistata in anticipo) (video 3). Qui facciamo conoscenza, tra gli altri, di Raimunda (Penélope Cruz), donna delle pulizie, che qualche giorno dopo, tornata a Madrid, scopre che la figlia Paula (Yohana Cobo) ha ucciso quello che riteneva essere suo padre, Paco (Antonio de la Torre), per reagire a un suo tentativo di violenza nei suoi confronti. Dopo un primo momento di disperazione, Raimunda non si perde d'animo: mette il corpo del marito nel freezer di un ristorante sotto casa, il cui proprietario è al momento assente, e che lei stessa si mette a gestire, con l'aiuto di alcune vicine di casa anch'esse più o meno single o prostitute (comunque senza uomini). Durante una successiva visita al villaggio, Raimunda, sua sorella Sole (Lola Duenas)e la figlia Paula fanno visita alla vecchia zia (Chus Lampreave), anch'essa di nome Paula, che viene accudita da una vicina, Agustina. La zia insiste nel dire di aver visto la madre di Raimunda, Irene (Carmen Maura), morta anni addietro insieme al marito nell'incendio di una capanna. Presto si capisce che Irene non è affatto morta, al punto che Sole la porta di nascosto a Madrid, nascondendola a casa sua. Ma Raimunda non tarda a scoprirla, e da questo momento il centro dell'attenzione si sposta su Irene, le sue due figlie, e Agustina, che sta morendo di cancro. Dopo che il corpo del marito di Raimunda viene sbrigativamente trasferito dal freezer in una fossa in mezzo a un bosco, pian piano, tra i racconti di Irene e quelli di Agustina, veniamo a sapere la verità sul passato di tutti: Raimunda era stata messa incinta dal padre, cui la madre non trovava la forza di opporsi; e Irene, oltre a scoprire l'abuso perpetrato dal marito su Raimunda, aveva anche scoperto la sua relazione con la madre di Agustina - inducendola a dar fuoco alla capanna dove si trovavano i due amanti. Ma Irene non è "tornata" solo per questo: verso la fine del film, si prenderà cura di Agustina, accompagnandola con dolcezza sino alla fine. Se quasi tutti i film di Come si vede, ancora una volta |

The movie opens on a view of a cemetery in na country village, with a strong wind sweeping the tombstones, which groups of women are carefully cleaning (one of them, Agustina (Vlanca Portillo) is actually taking care of her own grave, which she has bought in advance ...)(video 3). Here we get to know, among others, Raimunda (Penélope Cruz), a cleaning woman, who, a few days later, on her return to Madrid, finds out that her daughter, Paula (Yohana Cobo) has killed the man who, she thought, was her father, Paco (Antonio de la Torre), in an attempt to defend herself against his sexual violence. After being overcome with despair, Raimunda does not lose her heart: she hides her husband's body in the freezer of a nearby restaurant, whose owner is away for the time being, and even starts running the same restaurant with the help of a few neighbours, who are themselves either single or prostitutes (no man is in view). During a later visit to the village, Raimunda, her sister Sole (Lola Duenas) and her daughter Paula go to see an old aunt (Chus Lampreave), whose name is Paula too, who is looked after by a neighbour, Agustina. Aunt Paula insists on saying that she had seen Raimunda's mother, Irene (Carmen Maura), who died years before together with her husband when a cottage caught fire. It is soon clear that Irene is not dead at all, so that Sole takes her to Madrid and hides her at her home. Raimunda, however, soon finds her out, and from this moment on the focus moves to Irene, her two daughters, and Agustina, who is dying of a cancer. After Raimunda's husband's body is quickly disposed of, moving it from the freezer to a wood, through Irene's and Agustina' stories we find out that the truth about everybody: Raimunda had been abused and left pregnant by her father, with her mother Irene failing to find the courage to expose him; and Irene, in addition to finding out about this abuse, had also found out his relationship with Agustina's mother - eventually deciding to set fire to the place where the two lovers used to meet. But Irene has not "come back" just for this: towards the end of the movie, she will take care of a dying Agustina, standing by her side till the end. If almost all of As can be seen, once again |

Video 1 Video 2

Video 3 Video 4

Volver (2006)

| Il tema del ritorno, e

del passato che ritorna, è nuovamente al centro del successivo film di Per la prima volta, il protagonista principale è uomo eterosessuale, un regista, Harry Caine (Lluis Homar), che, dopo un incidente in cui ha perso la vista, lavora ora come sceneggiatore, aiutato da una valente collaboratrice, Judit (Blanca Portillo). Harry si trova a rifiutare una proposta per un film da parte di un misterioso Ray X (Rubén Ochandiano), perchè in realtà Ray X è il figlio di Ernesto Martel (Luis Goméz), il ricco finanziatore dell'ultimo film diretto da Harry, e amante della protagonista del film, la bellssima Lena (Penélope Cruz). Spinto dal figlio di Judit, Diego (Tamar Novas) a ricordare il passato, Harry rivivrà la sua passione per Lena, prigioniera della terribile gelosia di Ernesto, e l'incidente d'auto che fu la causa della sua cecità, ma anche della perdita di Lena. E in questi ritorni al passato anche Judith confesserà a Diego, suo figlio e collaboratore di Harry, che lui è figlio di una relazione che Judith aveva avuto con Harry stesso. Ma su tutto domina pur sempre la meraviglia e il mistero del cinema, mezzo espressivo ma anche, e forse soprattutto, ponte che aiuta ad attraversare la vita e ad amarla fino in fondo. Nel video 3 qui sotto, Harry racconta, come possibile trama di un film, la storia di Arthur Miller, che, dopo il divorzio da Marilyn Monroe, ebbe un figlio con la sindrome di Down, che non volle mai vedere; solo molti anni dopo lo incontrò ad una conferenza, senza riconoscerlo. Mentre Harry racconta questa storia, vediamo sullo sfondo Diego, ancora inconsapevole, come Harry, della relazione che li lega come padre e figlio. Le due storie parallele sono messe in scena con il contrasto tra Harry, in primo piano, e Diego, sullo sfondo ... Il potere taumaturgico del cinema è uno dei punti centrali del film: non a caso, alla fine, il regista Harry dice, toccando lo schermo: "Riproducilo [play] fotogramma per fotogramma, così che duri più a lungo". |

T For the first time, the main character is an heterosexual man, a film director, Harry Caine (Lluis Homar), who, after being involved in an accident nad losing his sight, now works as a screenwriter, with the help of a skilful assistant, Judit (Blanca Portillo). Harry decides to refuse a film proposal from a mysterious Ray X (Rubén Ochandiano), since Ray X is actually the son of Ernesto Martel (Luis Goméz), who was both the wealthy person who had financed Harry's last movie, and the lover of that movie's protagonist, the beautiful Lena (Penélope Cruz). Urged by Judit's son, Diego (Tamar Novas) to remember the past, Harry will recollect his passion for Lena, who had suffered from Ernesto's terrible jealousy, and the car accident which caused his blindness as well as the loss of Lena. And while the past resurfaces, Judit, too, will reveal to Diego, her son and Harry's co-worker, that he is actually Harry's son. Once again, present and past merge, as do reality and fiction, visible and invisible - and it is not by chance that the representation of reality, reaching a state of voyeurism, takes central place through the various forms that cinema can take. In the first place, film-making itself: Almodóvars cinephilia fills this movie, even more than in other works of his, with direct and indirect quotations and references, from Journey to Italy (by Roberto Rossellini, Italy/France 1953) to Elevator to the gallows (by Louis Malle, France 1957), from Peeping Tom (by Michael Powell, GB 1960) to Leave her to heaven (by John M. Stahl, USA 1945), among others. But the act of seeing (or rather, watching) includes photography, too, as well as paintings (Magritte) and even the X-Rays of Lena's body after the accident. This time, hoever, all these ways of seeing, interpreting and re-crearting reality are at the service of a few themes, which are typical of Almodóvar 's sensibility, that are introduced here in more restrained, almost detached, ways: love, desire, passion, death and a lust for life, pain which goes together with pleasure, and the sense of the body, now no longer an object or a subject of desire but also the place where disease and ageing are displayed. Above all this, however, hovers the wonder and mystery of cinema, a way of expression but also, and maybe mainly, a bridge which helps to cope with life and love it to the full. In video 3 below, Harry tells, as the plot for a possible movie, the story of Arthur Miller, who, after divorcing Marilyn Monroe, had a son with Down's syndrome, whom he always refused to see: only many years later did he meet him at a lecture, withouth recognizing him. As Harry tells this story, we see in the background Diego, who is still unaware, as Harry is, of the relationship that binds them together as father and son. The two parallel stories are stages through the contrast bertween Harry, in the foreground, and Diego, in the background ... Cinema as salvation is one of the main themes of this movie: at the very end, Harry the film director touches the screen and says," |

| 12.

Verso nuove consapevolezze Al suo ventesimo film, con Julieta Tutto ciò è ben visibile sin dalla trama, che, pur presentando parecchi personaggi e una fitta rete di relazioni e non mancando di colpi di scena, appare comunque più lineare: non più figure grottesche, non più intrighi e segreti, non più "sesso, droga e rock'n roll": qui si parla della vita vera di personaggi definiti nella loro specificità (vedi il trailer nel video 1 qui sotto). Julieta (Emma Suarez), giunta alle soglie dell'età di mezzo, sta per lasciare Madrid per seguire il suo partner Lorenzo (Dario Grandinetti) in Portogallo, quando (vedi il video 3 qui sotto) l'incontro casuale con un'amica della figlia, Beatriz (Michelle Jenner) riapre una dolorosa ferita: Julieta non vede Antia (Blanca Parés) da tredici anni, ha fatto di tutto per dimenticarla, ma ora il passato ritorna con prepotenza: Antia è madre di tre figli e vive in Svizzera. Julieta decide di non partire più e si mette a scrivere una lunga lettera alla figlia - che nel film diventa un doloroso flashback della sua vita. Vediamo dunque Julieta, giovane professoressa di lettere antiche (Adriana Ugarte), che, diretta verso il suo nuovo lavoro, incontra sul treno un uomo, che tenta di iniziare una conversazione con lei. Infastidita, Julieta lascia il compartimento e incontra un giovane pescatore, Xoan (Daniel Grao). Il treno frena bruscamente: l'uomo che Julieta aveva lasciato solo nel suo compartimento si è suicidato. Quasi ad esorcizzare questo shock, Julieta ha un rapporto sessuale con Xoan, in cui resta incinta. Qualche mese più tardi, Julieta raggiunge Xoan, che nel frattempo è rimasto vedovo della moglie in coma da anni, e lo sposa, entrando così nella sua vita, e venendo a conoscere Ava (Inma Questa), amica e in passato amante di Xoan, e la domestica Marian (Rossy De Palma), che aiuta Xoan nelle faccende domestiche. Tre anni dopo, Julieta va a trovare i genitori con la figlia Antia, e apprende che la madre è gravemente ammalata e che il padre ha assunto una donna come badante, ma con la quale ha anche intrecciato un rapporto - cosa che Julieta non accetta volentieri. Passa ancora qualche anno. Antia, ormai adolescente, parte per un campeggio, e la sera stessa Julieta, dopo un colloquio con la domestica, rinfaccia a Xoan la sua vecchia relazione con. Xoan esce in mare per pescare, ma nel corso di una burrasca perde la vita. Julieta torna a Madrid, e trova un po' di conforto solo nella figlia Antia e nell'amica Beatriz, che Antia ha conosciuto in campeggio. Ma quando Antia compie diciotto anni, decide di recarsi in un ritiro spirituale nei Pirenei, e in tal modo scompare dalla vita di Julieta, facendo perdere le sue tracce. Julieta, sconvolta e disperata, non trova pace. Ritrova in ospedale, ammalata di sclerosi multipla e ormai in fin di vita, Ava, che le rivela come Antia le abbia sempre ritenute in un certo senso responsabili della morte del padre. Nel frattempo, Julieta intreccia una relazione con Lorenzo (Dario Grandinetti), conosciuto in ospedale, e sembra godere di un momento di serenità. Ma il passato ritorna ancora una volta: quando casualmente incontra di nuovo Beatriz, l'amica della figlia, questa le rivela che lei ed Antia erano legate da un rapporto ben al di là dell'amicizia, e che Antia, maggiorenne, aveva deciso di troncare ogni relazione con lei per rifarsi una nuova vita. L'arrivo di una lettera di Antia avvia Julieta verso una nuova fase: Antia ha perso il figlio più grande, e solo ora capisce cosa significhi il dolore che ha causato alla madre con il suo silenzio. Il film termina con Julieta e Lorenzo, che in auto si recano a trovare Antia in Svizzera: forse, un futuro riconciliato ... In questo caso la dettagliata descrizione della trama serve soprattutto a mettere in evidenza la sottile rete di emozioni che scorre sotto questa serie di eventi e di rapporti, la sofferenza che attanaglia tutti i personaggi. In particolare, i sentimenti con cui Julieta deve fare i conti sono tanti: i sensi di colpa, per il suicidio di quell'uomo a cui non aveva prestato ascolto sul treno, per il marito accusato di infedeltà, per la figlia scomparsa dalla sua vita; la rabbia per questa scomparsa; la solitudine, che a più riprese la sovrasta. Attorno a lei scorrono e terminano vite che solo in parte lei riesce a capire ed accettare: la malattia e la morte la toccano da vicino in più occasioni (il marito, la sua amica Ava, la madre malata di Alzheimer); a fatica accetta che il padre abbia trovato una nuova compagna; e tarda a realizzare di non essere veramente stata vicino alla figlia. Eppure, tutte queste colpe non sono veramente e completamente tali: è come se il fato avesse predestinato lei e i suoi compagni di vita a fare esperienze tutte in qualche modo segnate dall'incomprensione, dal dolore, dalla solitudine. Ma queste sofferenze non si esprimono più in termini di melodramma: sono ora più riservate e più pudiche, come se il dolore stesso avesse asciugato le lacrime (e in un'intervista Almodóvar ha confessato di aver proibito alle sue attrici di piangere durante le riprese, permettendo loro di sfogare fisicamente la loro sofferenza solo quando gridava: "Stop!")(Nota 4). Solo alla fine, quando Julieta riceve notizie dalla figlia, si squarcia questo senso di ineluttabile dolore per far posto ad un possibile senso di perdono, di tenerezza, di riconciliazione: forse per Julieta e Antia, ora unite nella consapevolezza e nella sofferenza, si apre finalmente un percorso di ritorno alla vita. |

12. Towards a new

consciousness For his twentieth movie, Julieta, All this is clearly visible in the story itself, which, although introducing several characters, a network of relationships and a few twists and turns, looks nonetheless more linear: no more grotesque figures, no more plots and secrets, no more "sex and drugs and rock'n'roll": here we have a slice of true life and a range of psychologically defined characters (see the trailer in video 2 below). Julieta (Emma Suarez), a middle-aged woman, is about to leave Madrid to follow her partner Lorenzo (Dario Grandinetti) to Portugal, when (see video 3 below) she casually meets her daughter's friend, Beatriz (Michelle Jenner): this opens up an old sore, as Julieta hasn't met her daughter Antia (Blanca Parés) for thirteen years, has done everything to forget her, but now the past comes back: Julieta learns that Antia is a mother of three children and lives in Switzerland. Julieta then decides to stay in Madrid and starts writing a long letter to her daughter - which in the movie becomes a painful flashback of her life. We then see a much younger Julieta (Adriana Ugarte), a teacher of humanities, who, while travelling by train to take up her new job, meets a man, who tries to start a conversation with her. Annoyed by his presence, Julieta leaves her compartment and meets a young fisherman, Xoan (Daniel Grao). The train brakes sharply: the man Julieta has just met has committed suicide. Almost as a way to exorcise this shock, Julieta and Xoan make love and she gets pregnant. A few months later, Julieta joins Xoan at his home. The man's wife has just died after being comatose for years, and they marry. Julieta thus gets to know Ava (Inma Questa), a friend and past lover of Xoan's, and Marian (Rossy De Palma), who is Xoan's daily help. Three years later, Julieta goes to visit her parents with her daughter Antia, and learns that her mother is seriously ill and is looked after by a young woman, who is also clearly her father's new partner - which Julieta cannot really accept. A few years go by. Antia, now a teenager, leaver for a summer camp, and on the same night Julieta, after a conversation with Xaon's daily help, has a row with Xoan about his past relationship with Ava. Xoan goes out fishing but is caught in a storm and loses his life. Julieta goes back to Madrid, and find some comfort only in Antia and her friend Beatriz, whom Antia met at the summer camp. However, on Antia 's eighteenth birthday, the girl decides to leave for a religious retreat in the Pyrenees, and in this way disappears from Julieta's life. Julieta, at a loss as to how to find her daughter, is in desperation. She meets Ava in a hospital, where the latter is dying of multiple sclerosis. Ava tells her that Antia has always considered them responsible for Xoan's death. In the meantime, Julieta starts a relationship with Lorenzo (Dario Grandinetti), a man she met at the hospital, and seems to enjoy a moment of happiness. But once more the past comes back to her: when she casually meets Beatriz, her daughter's friend, for a second time, she learns that Beatriz and Antia had been much more than just friends, and that Antia had decided to break off their friendship and start a new life. When Julieta later receives a letter from Antia, she learns that her daughter has just lost her older child, and, as a result, she is now in a position to appreciate the pain that she inflitced on her mother through her disappearance. The movie ends as Julieta and Lorenzo drive to Switzerland, where Julieta may eventually be reconciled with her daughter ... In this the detailed description of the plot helps us mainly to highlight the subtle network of emotions underlying this series of events and relationships, the pain all the characters experience. In particular, the feelings Julieta has to cope with are of different kinds: the sense of guilt, for the suicide of the man she hadn't cared for on the train, for her husband she considers guilty of infidelity, for her daughter, disappeared from her life; the anger caused by this disappearance; the loneliness which she has to endure. Several people carry on and end their lives around her - lives she can hardly understand and accept: disease and death hit her closely at different times (her husband, his friend Ava, her mother suffeering from Alzheimer's disease); she can hardly accept the fact that her father has found a new partner; and she is late in realizing that she hasn't really been close enough to her daughter. And yet, she is not really and completely responsible for all these events: it is as if fate had doomed her and the people around her to go through life experiences laden with incomprehension, pain and loneliness. However, such suffering is not expressed in terms of melodrama: it is now more restrained, as if pain had drained all tears: Only at the end, when Julieta finally hears from her daughter does this pain seem to dissolve to be replaced by a possible sense of forgiving, tenderness and reconciliation: perhaps Julieta and Antia, now joined together by awareness and pain, can now slowly return to life. |

|

Video 1 Video 2 Video 3 Julieta (2016) |

|

| Con il successivo

Dolor y gloria

Almodóvar

torna, con gli stessi toni trattenuti e riflessivi, ai ricordi

d'infanzia e dunque a rivisitare quelle esperienze, cruciali per la sua

vita personale e professionale, che aveva così spesso tratteggiato in

tante sue opere. E non a caso sceglie come protagonista Antonio

Banderas, l'attore che forse più di tutti è stato il simbolo dell'Almodóvar

"prima fase", a cominciare da La legge del desiderio;

e tutto il film è punteggiato di riferimenti più o meno espliciti

non solo ai suoi film precedenti, ma anche agli scrittori, ai

poeti, ai drammaturghi che hanno plasmato la sua sensìbilità, nonchè,

ovviamente, alle infinite fonti cinematografiche, dalle figurine con i

volti di Tyrone Power e Robert Taylor ai riferimenti a Niagara

(di Henry Hathaway, USA 1953)

e Splendore nell'erba (di Elia Kazan, USA 1961), nonchè ai film

noir americani, ora però

rivisitati con nostalgia e quasi con tenerezza, senza l'ossessione degli

elementi più macabri o persino morbosi cui era stato così sensibile in

gioventù (vedi il trailer nel video 1 qui sotto). Banderas ha qui il ruolo di Salvador, un regista in crisi creativa e personale, che soffre di una serie di malattie e disturbi (ben descritti in una gustosa sequenza di disegni animati, e dei quali Salvador stesso dice: "I giorni in cui diversi dolori convergono credo in Dio e lo prego; i giorni in cui soffro di un solo dolore sono ateo"). Sin dall'inizio vediamo dunque Salvador lasciarsi andare ai ricordi, in particolare al ricordo della madre (Penélope Cruz) - ed è solo il primo di una serie di flashback attivati dalla vista di un oggetto, da momenti di riflessione, e persino dall'effetto della droga che per la prima volta Salvador assume. Ma questi ricordi non sono sempre piacevoli: riportano alla mente la Spagna del dopoguerra, con la povertà delle aree rurali; la presenza invasiva della religione (con le immaginette, i rosari, la devozione della madre); l'esperienza del seminario, dove da bambino, Salvador avrebbe voluto solo studiare e imparare, mentre i preti lo avevano scelto per la sua bella voce, costringendolo persino a saltare degli esami; la scoperta dell'(omo)sessualità. E questi non sono solo ricordi, ma sentimenti e sofferenze che accompagnano anche il presente: il rapporto difficile con l'attore che era stato il protagonista di un suo famoso film trent'anni addietro; l'incontro con un suo vecchio amore, ormai sposato e lontano; e lo stesso rapporto con la madre, fatto di rimorsi ("Non sono mai stato il figlio che tu volevi che fossi" e "Non sei mai stata orgogliosa di me", le dice mentre la cura amorevolmente, ormai prossima alla fine). Ma questi ricordi non sono vissuti con dolore, rabbia o rimpianto, ma piuttosto con un distacco quasi stoico, con una tenera nostalgia, con una rassegnazione serena - e questi sentimenti si riflettono nel disegno dei personaggi, che ora sembrano essere venuti a patti con le loro scelte sessuali; nei risvolti della trama, quasi inesistente, e in cui gli incontri fortuiti non sono occasione di traumi e ossessioni ma solo occasioni di dialogo con se stessi; e, infine, in scelte stilistiche nuove, con la rinuncia all'usuale tavolozza di colori accesi, quasi accecanti, e la scelta di tonalità più distese. Un'opera chiaramente autobiografica (un testamento spirituale?), dunque, e insieme una riflessione sulla gloria raggiunta, e forse ancora di più sui dolori passati e presenti che l'hanno accompagnata. "Il film a cui ho pensato di più mentre guardavo Dolor y gloria, più ancora che 8 1/2 - un riferimento ovvio sottolineato dal poster del film di Fellini appeso nell'ufficio dell'assistente personale di Salvador - è stato il capolavoro Mia madre di Nanni Moretti. Entrambi i film vagano attorno alle afflizioni, alle incertezze, ai rari momenti di sollievo di un regista in crisi, ed entrambi culminano emotivamente nel ritratto di un regista che si prende cura di una madre sofferente" (Nota 5). |

In his next movie, Dolor y gloria,

Almodóvar

comes back, wuth the same restrained and reflective mood, to his

childhood recollections, thus revisiting those experiences, crucial for

both his personal and professional life, that he had so often portrayed

in so many of his previous works. It is not by chance that he chooses as

the main character Antonio Banderas, the actor who has mostly been the

symbol of the "first phase"

Almodóvar, starting

from Law of desire; and the whole

movie is dotted with more or less explicit references not just to his

previous movies, but also to the writers, poets, playwrights who shaped

his sensibility, as well as to the endless cinematic sources, from the

picture-cards showing actors' faces like Tyrone Power and Robert Taylor

to the references to

Niagara

(by Henry Hathaway, USA 1953) and Splendor in the grass (by Elia Kazan, USA 1961),

plus the American film noir - all of which are now revisited with

nostalgia and even tenderness, without the obsession of the darker and

even morbid elements which he had so much fondled in his youth (see the

trailer in video 2 below). Here Banderas plays the role of Salvador, a film director undergoing a creative and personal crisis, who suffers from a series of diseases and troubles (well described in an amusing sequence of animated cartoons, about which Salvador says, “The days when several aches converge I believe in God and pray to him; the days I only suffer of one pain I’m an atheist”). Right from the start we see Salvador indulging in recollections, particularly about his mother (Penélope Cruz) - and it is just the first in a series of flashbacks activated by the sight of an object, by moments of reflection, and even by the effects of the drugs that Salvador now starts taking. However, these recollections are not always pleasant ones: they bring to mind the post-war Spain - poor rural areas; the pervasive presence of religion (votive images, rosaries, his mother's devotion); the experience of the seminar, where, as a child, Salvador would have liked to just study and learn, while the priests had singled him out for his beautiful voice, even obliging him to miss some exams; the discovery of (homo)sexuality. And these are not just recollections, but feelings and pain that bear on the present, too: the difficult relationship with the actor who had been the protagonist of one of his famous movies many years before; the meeting with one of his former lovers, who is now married and living abroad; and the same relationship with his mother, made up of remorse ("I was never the son you wanted me to be" and "You were never proud of me”, he says, as he affectionately takes care of her, now approaching the end). However, such recollections are not experienced with pain, anger or regret, but rather with an almost stoic detachment, with tender nostalgia, with a calm resignation - and these feelings are reflected in the psychology of the characters, who now seem to have come to terms with their sexual choices; in the design of the plot, which is almost non-existent, and in which the chance meetings do not imply shock or obsession but are opportunities for a dialogue with oneself; and, finally, in new stylistic choices, which give up the usual palette of bright, nearly blinding colours in favour of more toned-down hues. Thus this is a clearly autobiographical work (a spiritual legacy?), as well as a reflection on the glory now attained, and even more on the present and past pain that has come with it. "The movie I thought about most while watching Pain and Glory, even more than 8½ - an obvious reference underlined by the poster of Fellini’s film hanging in the office of Salvador’s personal assistant—was Nanni Moretti’s masterful Mia madre. Both movies wander around the afflictions, uncertainties, and scarce moments of solace of a filmmaker in crisis, and both emotionally culminate in the depiction of a filmmaker caring for an ailing mother". (Note 5). |

Video 1 Video 2

Dolor y gloria - Pain and glory (2019)

|

13. Conclusion "Pedro Almodóvar è una specie di paradosso ... Celebrato e denigrato dai critici come serio e superficiale, politico e apolitico, morale e immorale, femminista e misogino, sperimentale e sentimentale, universale e provinciale, Almodóvar ha tracciato una rotta dai margini controculturali della sua natia Spagna ad un mainstream internazionale che ... non è riducibile alla sua modalità dominante hollywoodiana" (Nota 2). |

13. Conclusion "Pedro Almodóvar is something of a paradox ... Celebrated and denigrated by critics as serious and superficial, political and apolitical, moral and immoral, feminist and misogynist, experimental and sentimental, universal and provincial, Almodóvar has charted a path from the countercultural margins of his native Spain to an international mainstream which ... is not reducible to its dominant Hollywood modality" (Note 2). |

Note/Notes

(1) All about sexuality, p. 17.

(2) Epps B., Kakoudaki D. (eds.) 2009. All about Almodovar. A passion for cinema, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, pp. 32 e/and 10.

(3)

|

Per

saperne di più ... * Dal sito Movieplayer.it: - Pedro Almodóvar: I 10 migliori film del regista, con numerosi altri collegamenti * Dal sito Film.it: - Pedro Almodovar, con biografia, filmografia e collegamenti ad articoli e video * Da Wikipedia: - Pedro Almodóvar * Dal canale YouTube di ScreenWeek TV: - I 5 migliori film di Pedro Almodóvar * Dal sito Mymovies.it: - Filmografia di Pedro Almodóvar: critica, premi, foto, articoli e news * Dal sito ComingSoon.it: - Pedro Almodóvar: filmografia, video, foto, news, trame e critica |

|

Want to know more? * From the British Film Institute YouTube channel: - Pedro Almodóvar in conversation - an in-depth interview * From the indiewire.com website: - The 10 best films by Pedro Almodóvar * From the BAFTA Guru YouTube channel: - Pedro Almodóvar: On directing - Pedro Almodóvar: On finding his inspiration * From Emmet Gusikowski's YouTube channel: - Pedro Almodóvar interview (1994) * All about Almodóvar - A passion for cinema * A Spanish labyrinth: The films of Pedro Almodóvar * From the Senses of Cinema website: - Pedro Almodóvar * From The New Yorker website: - Pedro Almodóvar: various articles * From the moviesin203.org website: - Pedro Almodóvar's renegotiation of Spanish identity * From The New York Review of Books website: - The women of Pedro Almodóvar by Daniel Mendelsohn |

|

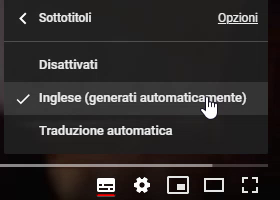

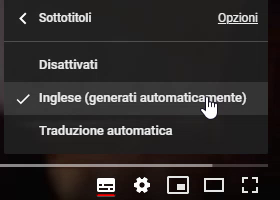

Come visualizzare sottotitoli nei

videoclip di YouTube Molti videoclip su YouTube forniscono sottotitoli generati automaticamente. Ecco come procedere per visualizzarli: 1. Se i sottotitoli sono disponibili, in basso a destra compare l'icona 2. Se si desidera cambiare lingua, cliccare sull'icona accanto, "Impostazioni"  3. Cliccare su "Sottotitoli". Comparirà questo altro menu:  4. Cliccare su "Inglese (generati automaticamente)". Comparirà questo menu:  5. Cliccare su "Traduzione automatica" e nell'elenco delle lingue cliccare sulla lingua desiderata:  |

How to visualize subtitles in YouTube video

clips Several YouTube videos clips provide automatically generated subtitles. This is how to proceed to visualize them: 1. If subtitles are available, while in "play" mode click this icon 2. If you wish to change the language, click the nearby icon "Settings"  3. Click "Subtitles" and you will get this menu:  4. Click "English (auto-generated). This menu will appear:  5. Click "Auto-translate" and in the list of languages click the desired language:  |

Torna all'inizio della pagina Back to start of page