Interactive workshops

|

Laboratori interattivi Interactive workshops |

| I generi

cinematografici: origine, funzioni, evoluzione Seconda parte |

Film genres: origin,

functions, evolution Part 2 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Note: - E' disponibile una versione pdf di questo Dossier. - Il simbolo |

Notes: - A pdf version of this Dossier is available; also available as a printable document equipped with QR codes to access YouTube videos directly from the printed text. - The symbol |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Indice N.B. Per un esame preliminare di questo argomento, si veda il Dossier I generi cinematografici. Prima parte 1. Introduzione 2. Perchè sono utili e necessarie "etichette" di genere? 3. Alla ricerca di criteri di classificazione Esempi di categorie, ampie e ristrette 4. Il film come testo: le convenzioni di genere 4.1. Lo stile 4.2. La colonna sonora 4.3.L'ambientazione 4.4. L'iconografia 4.5. Storie/Temi e le loro narrazioni 4.6. I personaggi e gli attori/le attrici 5. Il film come testo: strutture narrative 6. Il film come testo: gli approcci semantico-strutturali 7. Ripetizione e variazione Seconda parte 8. I generi come elementi socioculturali 9. Oltre il testo cinematografico: gli usi dei generi 10. Non solo generi ... 11. Le funzioni dei generi 11.1. La funzione economica 11.2. La funzione socio-culturale 11.3. La funzione comunicativa Terza parte 12. Una prospettiva storica 12.1. La prospettiva evoluzionista 12.2. L'evoluzione finale: la parodia e la satira 12.3. Oltre la visione evoluzionista 12.4. La genesi di un genere 13. Generi e "cicli" 14. Fine dei generi cinematografici? 15. La mescolanza dei generi e l'ibridazione 16. Il genere - una categoria universale? 17. Conclusione |

Contents N.B. For a preliminary overview of this topic, see the Dossier Film genres. Part 1 1. Introduction 2. Why are generic labels useful and necessary? 3. In search of classification criteria Examples of categories, broad and narrow 4. Film as text: genre conventions 4.1. Style 4.2. Soundtrack 4.3. Setting 4.4. Iconography 4.5. Stories/Themes and their narratives 4.6. Characters and actors/actresses 5. Film as text: narrative structures 6. Film as text: semantic-structural approaches 7. Repetition and variation Part 2 8. Genres as sociocultural elements 9. Beyond film text: the uses of genres 10. Not just genres ... 11. The functions of genres 11.1. The economic function 11.2. The socio-cultural function 11.3. The communicative function Part 3 12. A historical perspective 12.1. The evolutionary perspective 12.2. The ultimate evolution: parody and satire 12.3. Beyond the evolutionary view 12.4. Genesis of a genre 13. Genres and "cycles" 14. The end of film genres? 15. Genre mixing and hybridization 16. Genre - a "universal" category? 17. Conclusion |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

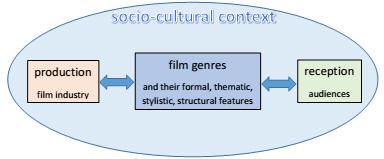

8. I generi come elementi socioculturali Abbiamo già discusso come i generi cinematografici siano definiti non nel vuoto, come idee astratte o da singole persone o istituzioni, ma siano, prima di tutto, il risultato di una sorta di "accordo" tra l'industria cinematografica (il lato "produttivo", da un lato, e il pubblico (il lato "ricettivo") dall'altro, basato, ovviamente, sul presupposto che i film sono realizzati per realizzare un profitto, e questo profitto proviene dal pubblico. Il "film come prodotto" diventa così un ponte tra produzione e consumo, un codice condiviso, simile a qualsiasi altro prodotto mass-mediale, e un potente mezzo di comunicazione (soprattutto oggi, quando le comunità fisiche sono unite da una miriade di comunità Internet). Tuttavia, abbiamo accennato al fatto che i discorsi sui film e sui generi cinematografici non si limitano ai produttori e al pubblico, ma implicano la partecipazione e l'interazione di una serie di altri "parti interessate", dai critici cinematografici agli studiosi di cinema, dalle agenzie pubblicitarie alle istituzioni culturali. Quindi la stessa definizione di "genere" deve includere i ruoli che tale concetto svolge in una varietà di contesti diversi: in altre parole, i generi cinematografici sono definiti e utilizzati all'interno di un contesto socio-culturale molto ampio, come mostra il grafico seguente: |

8. Genres as sociocultural elements We have already discussed how film genres are defined not in a vacuum, as abstract ideas or by single persons or institutions, but are, first and foremost, the result of a sort of "agreement" between the film industry (the "production" side), on the one hand, and the audiences (the "reception" side) on the other - based, of course, on the assumption that films are made to make a profit, and this profit comes from audiences. The "film as product" thus becomes a bridge between production and consumption, a shared code, much the same as any other mass-media product, and a powerful means of communication (particularly nowadays, when physical communities are joined by a host of virtual Internet communities). However, we have mentioned that the discourses about films and film genres are not limited to producers and audiences, but imply the participation and interaction of a number of other "stakeholders", from film critics to film scholars, from advertising agencies to cultural institutions. Thus the very definition of "genre" must include the roles that such a concept plays in a variety of different contexts: in other words, films genres are defined and used within a very broad socio-cultural context, as the following graph shows: |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Mentre dovremmo sempre "tenere d'occhio" le caratteristiche formali,

strutturali, stilistiche di un genere cinematografico (cioè il film

come testo, di cui abbiamo discusso nella

Prima parte di questo Dossier), dobbiamo

ora considerare la natura comunicativa dei generi cinematografici - in

altre parole, per cogliere appieno la natura dei generi cinematografici

dobbiamo esplorare come vengono utilizzati da utenti diversi per scopi

diversi. Questo ci porterà in seguito a considerare in modo più

approfondito quali a funzioni (economiche, socioculturali, comunicative)

assolvano all'interno del contesto socioculturale complessivo in cui

sono inseriti. 9. Oltre il testo cinematografico: gli usi dei generi Per apprezzare appieno i diversi modi in cui viene utilizzato lo stesso testo filmico, possiamo partire (seguendo Altman e Moine, Nota 1) dalle modalità di presentazione, ovvero dai diversi luoghi (fisici, ma anche culturali) in cui il film viene proiettato e "consumato" da un pubblico. Proiettare un film in un "cinema d'essai" piuttosto che in un locale specializzato in film pornografici o in un festival cinematografico specializzato in un particolare "tema" (dai film di "alpinismo" alle tematiche LGBTQ+, dai film sul cambiamento climatico alle registe donne), finisce inevitabilmente per descrivere quel film (anche se solo temporaneamente) con un'etichetta "di genere". Lo stesso si potrebbe dire quando i film sono citati e descritti in riviste specializzate e pubblicazioni "di categoria" (oltre, ovviamente, a riviste dedicate a programmi TV, o pubblicazioni destinate a un pubblico specifico, ad esempio gli adolescenti). A livello più generale, non è da sottovalutare il ruolo della critica nell'assegnare un film a un determinato genere, soprattutto perché le recensioni (che ormai fanno parte di molti siti di film su Internet) hanno un impatto diretto sui loro lettori, che poi possono diventare il pubblico di quel film. L'esempio spesso citato del film noir mostra come molti film americani del dopoguerra, che non erano stati in alcun modo etichettati in quel modo, furono descritti per la prima volta da diversi critici francesi come noir, un aggettivo che era stato usato per qualche tempo in Francia per riferirsi a romanzi che avevano connotazioni "da giallo" (piuttosto che semplicemente "nere"). Quando l'etichetta "film noir" ha iniziato ad essere utilizzata e ha rapidamente acquisito lo "status" di genere, è stata adottata dall'industria come un modo conveniente per descrivere (e commercializzare) determinati tipi di film - e il genere ha quindi raggiunto nel tempo un'identità coerente, specialmente nella "New Hollywood" e, in seguito, con la tendenza "neo-noir" degli anni '80. Il ruolo della critica è alquanto mutato nel tempo, ed è ora integrato dal lavoro svolto dagli utenti di Internet che, in siti web, blog, chat online, social network, ecc., definiscono e ridefiniscono continuamente i generi cinematografici, mostrando come il pubblico è ora, in un certo senso, molto più attivo di un tempo, poiché contribuisce al discorso corrente sui film, con elevati livelli di popolarità, influenzando le scelte, le opinioni e i giudizi degli spettatori in aggiunta e al di là del lavoro svolto da critici e giornalisti cinematografici. Più in generale, anche i movimenti culturali hanno contribuito in modo significativo al riconoscimento dei film come "generi" specifici: il movimento LGBTQ+ è un ovvio esempio, ma lo stesso si può dire dei movimenti femministi, nel contribuire a stabilire la categoria piuttosto ampia dei "film al femminile", e dei movimenti per i diritti civili, nell'introdurre la "blaxploitation", termine che acquista periodicamente nuova risonanza, come mostra chiaramente il recente movimento "Black Lives Matter". Abbiamo già accennato alle classificazioni che i film danno da istituzioni come lo Stato, la Chiesa e altri organismi, ovvero i risultati della censura, che ha implicazioni molto diverse per i diversi paesi e nel tempo. Il modo in cui i film sono etichettati in relazione ai limiti di età ha ovviamente implicazioni per il genere a cui dovrebbero appartenere, specialmente se sono qualificati come film "per adulti". I produttori di solito sminuiscono l'importanza delle valutazioni nei loro materiali pubblicitari, fatta eccezione, ovviamente, per i film esclusivamente per adulti (ad esempio i film XXX, che beneficiano di una chiara visualizzazione della loro valutazione, come segno di appartenenza a un genere particolare e ben definito. Anche il significato del genere varia nel tempo, e man mano che nuovi generi emergono, le vecchie etichette svaniscono o, forse anche peggio, assumono una sorta di connotazioni peggiorative. La commedia "slapstick" e il "melodramma" sono stati per lungo tempo generi pienamente riconosciuti, ma nel corso del tempo hanno perso questa specificità e ora descrivere un film come "melodrammatico" è spesso considerato un giudizio negativo. Questo dovrebbe renderci consapevoli della variabilità dei significati del genere nel tempo e dell'importanza di non perdere di vista la storia e l'evoluzione di un genere per coglierne il pieno significato e le sue possibili connotazioni. Tali brevi considerazioni indicano il fatto cruciale che i generi cinematografici non hanno significati "unici" o "universali" condivisi da tutte le parti interessate ai film (come abbiamo visto, non solo produttori e consumatori), ma possono essere descritti in termini diversi da tali soggetti, secondo le loro finalità ed in relazione ai contesti in cui i generi stessi vengono identificati e descritti. 10. Non solo generi... Usare etichette "generiche", ovvero pubblicizzare e commercializzare un film assegnandolo a un genere specifico, non è sempre la prima scelta dei produttori, anzi, potrebbe essere il contrario. Se è vero che pubblicizzare un film come "un film pieno d'azione" o una "sexy commedia musicale" può fare molto per descriverne il tema e lo stile al pubblico, e quindi attivare le aspettative degli spettatori e, di conseguenza, un certo grado di fiducia che tali film saranno apprezzati almeno da un certo pubblico, è anche vero che gli studios, in particolare nell'era d'oro del "sistema di Hollywood", avevano diversi altri risorse che potevano utilizzare per promuovere i loro film e, soprattutto, per renderli il più diversi possibile dalla concorrenza. Uno studio potrebbe (e, in un certo senso, il moderno sistema di produzione può ancora) fare affidamento su attori sotto contratto, registi, personaggi, processi tecnici ("Technicolor", "Cinerama") e sui propri nomi commerciali (un a distribuzione "United Artists", una produzione "Paramount" ... - si veda il video qui sotto). L'utilizzo di queste risorse potrebbe (e può), da un lato, far risparmiare sui costi, ad es. evitando di produrre campagne pubblicitarie completamente nuove, e, dall'altro, fornire una continuità con i film precedenti che può essere sfruttata attraverso la familiarità del pubblico. Questo è uno dei motivi per cui, piuttosto che porre l'accento sul genere di un film (i generi, per definizione, non possono essere protetti da copyright), i produttori preferiscono molto spesso creare serie, cicli, sequel, remake, ecc. Utilizzare personaggi protetti da copyright come Indiana Jones, Rambo, Conan e la vasta gamma di "supereroi", da Batman e Superman in poi, si è rivelato estremamente redditizio, così come i nomi ricorrenti nei titoli, come Die Hard, Lethal Weapon, Star Trek, Predator, ecc. Indiana Jones fu presentato al pubblico per la prima volta come "il nuovo eroe dai creatori di JAWS e STAR WARS", sottolineando così il marchio dei produttori (i "creatori"). E lo stesso accade quando si promuove un film mettendo in risalto gli attori, i registi e gli sceneggiatori di precedenti film di successo. Negli ultimi decenni, inoltre, questo processo è diventato ancora più sofisticato, in quanto il film stesso è solo una sorta di "prodotto-base" al centro di miriadi di prodotti aggiuntivi o collaterali, dai CD e DVD ai dischi karaoke, dai videogiochi e giocattoli ai vestiti e persino al cibo e alle bevande - tutti recanti il marchio di base del franchising. |

While we should always "keep an eye" on the formal, structural,

stylistic features of a film genre (i.e. film as text, which we

discussed in Part 1 of this Dossier), the communicative nature of film genres now needs to

be considered - in other words, to fully grasp the nature of film genres

we must explore how they are used by different users

for different purposes. This will later lead us to consider in

more depth what functions (economic, socio-cultural,

communicative) genres serve within the overall socio-cultural context in

which they are embedded. 9. Beyond film text: the uses of genres To fully appreciate the different ways in which the same film text is used, we can start (following Altman and Moine, Note 1) from exhibition modes, i.e. the different venues (physical, but also cultural) where the film is projected and "consumed" by an audience. Showing a film in an "art cinema" rather than in a theatre specialising in pornographic movies or in a film festival specialised in a particular "theme" (from "mountaneering" films to LGBTQ+, from "climate change" movies to women directors), inevitably ends up describing that film (if only temporarily) with a "generic" label. The same could be said when films are mentioned and described in specialised magazines and "trade" publications (besides, of course, magazines devoted to TV programs, or publications targeted at specific audiences, e.g. teenagers). On a more general level, the role of critics in assigning a film to a particular genre is not to be underestimated, especially because reviews (which now make a large part of many web-based film sites) have a direct impact on their readers, who then may (or may not) become the audience of that film. The often-quoted example of film noir shows how many American post-war movies, which had in no way been labelled like that, were first described by several French critics as noir, an adjective which had for some time been used in France to refer to novels which had dark (rather than simply black) connotations. As the label "film noir" started to be used and quickly gained the "status" of a genre, it was taken up by the industry as a convenient way of describing (and marketing) certain kinds of movies - and the genre then achieved quite a consistent nature, in time too, with the "New Hollywood" and, later the "neo-noir" trend of the 1980s using it repeatedly. The role of critics has somewhat changed over time, and is now complemented by the work carried out by Internet users who, in web sites, blogs, online chats, social networks, etc., continually define and re-define film genres, showing how audiences are now, in a way, far more active than they used to be, since they contribute to the on-going discourse about films and are often very popular, influencing viewers' choices, opinions and judgments in addition to and beyond the work carried out by critics and film journalists. More generally speaking, cultural movements have also contributed in a significan way to the recognition of films as specific "genres": LGBTQ+ is an obvious example for gay movies, but the same could be said of feminist movements in helping to establish the (rather broad) category of "women's films" and civil rights movements in introducing "blaxploitation", a term which periodically gains new resonance, as the recent "Black Lives Matter" movement clearly shows. We have already mentioned the ratings films are given by institutions like the State, the Church and other bodies, i.e. the results of censorship, which has vastly different implications for different countries and across time. The way films are labelled in relation to age restrictions obviously has implications for the genre they are supposed to belong, especially if they are qualified as "adult" movies. Producers usually downplay the importance of ratings in their publicity materials, except, of course, for exclusively adult movies (e.g. the XXX films), which benefit fror their rating being clearly displayed, as a sign of belonging to a particular, well-defined genre. Genre significance also varies across time, and as new genres come to the fore, old labels fade away, or, perhaps even worse, assume a sort of pejorative connotations. "Slapstick" comedy and "melodrama" were for a long time fully recognized genres, but in the course of time have lost this specificity and now describing a film as "melodramatic" is often considered a negative judgment. This should make us conscious of the variance of genre meanings across time, and the importance of not losing sight of the history and evolution of a genre to capture its full significance and its possible connotations. Such brief considerations point to the crucial fact that film genres do not have "unique" or "universal" meanings shared by all the parties concerned with film (as we have seen, not just producers and consumers), but can be described in different terms by such parties, according to their purposes and in relation to the contexts in which genres themselves come to be identified and described. 10. Not just genres ... Using "generic" labels, i.e. publicizing and marketing a film by assigning it to a specific genre, is not always the first choice by producers - indeed, it may be the opposite. While it it true that advertising a movie as "an action-packed film" or a "sexy musical comedy" may go a long way in describing its theme and style to audiences, and thus activate viewers' expectations and, accordingly, a certain degree of confidence that such films will be appreciated by at least certain audiences, it is also true that studios, particularly in the golden era of the "Hollywood system", had several other assets that they could use to promote their films, and, most importantly, to make them as different as possible from the competition. A studio could (and, in a way, modern production system still can) rely on actors under contract, directors, characters, technical processes ("Technicolor", "Cinerama") and their own trade names (a "United Artists" release, a "Paramount" production ... - watch the video below). Using these assets could (and can), on the one hand, save costs, e.g. for producing completely new publicity campaigns, and, on the other hand, provide a continuity with previous films that can be exploited through the audiences' familiarity. This is one of the reasons why, rather than put an emphasis on the genre of a film (genres, by definition, cannot be copyrighted), producers very often prefer to establish series, cycles, sequels, remakes, etc. Using copyrighted characters like Indiana Jones, Rambo, Conan, and the wide range of "superheroes", from Batman and Superman onwards, has proved extremely profitable, as have been recurring names in titles, like Die Hard, Lethal Weapon, Star Trek, Predator, etc. Indiana Jones was first introduced to the audiences as "the new hero from the creators of JAWS and STAR WARS", thus stressing the brand name of the producers (the "creators"). And the same happens when a movie is promoted by highlighting the actors, the directors and the screenwriters of previous successful films. In the last few decades, moreover, this process has become even more sophisticated, as the movie itself is only a sort of "core product" at the centre of myriads of additional or side products, from CDs and DVDs to karaoke discs, from videogames and toys to clothes and even food and beverages - all bearing the basic trade mark of the "franchise". |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I più conosciuti "loghi" degli studi hollywoodiani/Best known logos of Hollywood studios |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Le industrie di Hollywood, così come i più recenti sistemi di

produzione, hanno sempre cercato di raccogliere i frutti dei loro film,

ben oltre i film stessi: ogni film portava con sé importanti risorse

come il nome dello studio, le star coinvolte, i personaggi e i titoli

dei film - tutti elementi che possono essere utilizzati più e più volte,

creando così una "catena" di vantaggi extra che si estende da un film

all'altro. 11. Le funzioni dei generi Esplorare la natura e il significato dei generi cinematografici è un compito multiforme che, pur considerando i film "generici" come testi, dovrebbe anche discutere le loro funzioni di potenti elementi dei contesti socio-culturali del cinema. Ciò implica la loro funzione economica (cioè il ruolo che svolgono nel modo in cui i film vengono prodotti seguendo le regole dei mercati di massa), la loro funzione socio-culturale (cioè come esprimono e mediano tra diverse visioni del mondo, ideologie e valori) e la loro funzione comunicativa (cioè come il pubblico interpreta un film, si relaziona con altri soggetti coinvolti nel cinema, e quindi contribuisce a plasmare i significati che i generi cinematografici alla fine esprimono) (Nota 2). 11.1. La funzione economica Uno dei principali vantaggi di stabilire generi riconosciuti, accettati e condivisi per l'industria cinematografica è l'opportunità che offre di standardizzare la produzione, ovvero di offrire al pubblico film che soddisfino le loro aspettative e possano quindi garantire un certo livello di successo al botteghino - tutto questo, ovviamente, nei limiti imposti dal principio fondamentale della "ripetizione e variazione" (come abbiamo visto nella Prima parte di questo Dossier) - un film di successo non può essere semplicemente replicato, ma deve offrire elementi di novità e sorpresa: "Il genere può essere considerato come un dispositivo pratico per aiutare qualsiasi medium di massa a impostare la produzione in modo coerente ed efficiente e a mettere in relazione la produzione con le aspettative dei clienti. Poiché è anche un dispositivo pratico per consentire ai singoli utenti dei media di pianificare le proprie scelte, può essere considerato come un meccanismo per strutturare le relazioni tra i due principali soggetti della comunicazione di massa". (Nota 3) L'idea di una sorta di produzione cinematografica "a catena di montaggio" appartiene sicuramente all'epoca d'oro degli studios di Hollywood, ma anche dopo il crollo di questo sistema, e nei decenni più recenti, è ancora ampiamente accettato che poter fare affidamento su un insieme di generi diversi può aiutare a prevedere le aspettative del pubblico (se non proprio controllare la domanda) e, allo stesso tempo, differenziare la produzione per soddisfare le esigenze e le preferenze di un pubblico diverso, con l'ulteriore, importante vantaggio di aggiungere standardizzazione e stabilità al processo produttivo. Tuttavia, rimane in primo luogo la questione di come identificare un "genere". Altman (Nota 4) chiama il processo attraverso il quale i produttori stabiliscono e gestiscono i generi "The Producer's Game", che ha alcune regole cruciali: "1. Dalle informazioni al botteghino, identifica un film di successo. 2. Analizza il film per scoprire cosa lo ha reso un successo. 3. Realizza un altro film adottando la presunta "formula di successo". 4. Controlla le informazioni al botteghino sul nuovo film e rivaluta di conseguenza la formula di successo. 5. Usa la formula rivista come base per un altro film. 6. Continua il processo a tempo indeterminato." Sebbene questo "Gioco" includa la parola "formula" come uno dei suoi principi fondamentali, non si tratta sicuramente di un insieme rigido di "regole" - al contrario, è un meccanismo altamente flessibile che si basa, da un lato, sul riferimento costante ai risultati di botteghino (cioè alla redditività) e, dall'altro, su una continua (ri)valutazione delle caratteristiche che rendono un film di successo. Lungi dal creare un insieme di "regole" per un genere, si sottolinea le qualità di "ripetizione e variazione" di cui abbiamo già discusso. In un certo senso, questo processo, che non si ferma mai ma è strettamente legato alla continua evoluzione dei mercati, è molto creativo, perché deve garantire un attento equilibrio tra il nuovo e il vecchio, tra i rischi e la garanzia del successo - insomma, non c'è standardizzazione senza innovazione (e viceversa). La storia del cinema abbonda di esempi della pratica del "Gioco del produttore". Anche al di fuori di Hollywood, il "gioco" è stato utilizzato più e più volte: negli anni '50 e '60, ad esempio, la società britannica Hammer si specializzò nella produzione di film di fantascienza e horror dopo il grande successo di "film-test" come, rispettivamente, L'astronave atomica del Dottor Quatermass e La maschera di Frankenstein (si vedano i video qui sotto). Dopo aver stabilito questi generi, la società fu in grado di standardizzare la produzione impiegando gli stessi registi, direttori della fotografia, scenografi e, naturalmente, attori (come Peter Cushing e Christopher Lee) - una "ricetta" che ha contribuito notevolmente a mantenere i costi al livello più basso possibile massimizzando i profitti. |

Hollywood industries, as well as more recent production systems, have

always tried to reap the full rewards of their films, well beyond the

films themselves: each film carried with it important assets like, as we

said, the studio's name, the stars involved, the characters and the film titles

- all elements that can be used time and time again, thereby creating a

"chain" of extra benefits that extends from a film to the next. 11. The functions of genres Exploring the nature and significance of film genres is a multi-faceted task which, while considering "generic" films as texts, should also discuss their functions as powerful elements of the socio-cultural contexts of cinema. This implies their economic function (i.e. the role that they play in how films are produced following the rules of mass markets), their socio-cultural function (i.e. how they express and mediate between different world views, ideologies and values) and their communicative function (i.e. how audiences interpret a film, relate to other subjects involved in cinema, and thus contribute to shape the meanings that film genres eventually express) (Note 2). 11.1. The economic function One of the main advantages of establishing recognized, accepted and shared genres for the cinema industry is the opportunity it offers to standardize production, i.e. to offer audiences movies that meet their expectations and can thus guarantee a certain level of box-office success - all this, of course, within the limits imposed by the master principle of "repetition and variation" (as we saw in Part 1) - a successful film cannot be simply replicated, but should offer elements of novelty and surprise: "The genre may be considered as a practical device for helping any mass medium to produce consistently and efficiently and to relate its production to the expectations of its customers. Since it is also a practical device for enabling individual media users to plan their choices, it can be considered as a mechanism for ordering the relations between the two main parties to mass communication." (Note 3) The idea of a sort of "assembly-line" production of movies certainly belongs to the "golden era" of Hollywood studios, but even after the collapse of this system, and in more recent decades, it is still widely accepted that being able to rely on a set of different genres can help predict audience expectations (if not really control demand) and, at the same time, differentiate production in order to meet the needs and preferences of different audiences, with the additional, important, bonus of adding standardization and stability to the production process. However, there remains the question of how to identify a "genre" in the first place. Altman (Note 4) calls the process by which producers establish and manage genres "The Producer's Game", which has a few critical rules: "1. From the box-office information, identify a successful film. 2. Analyse the film in order to discover what made it successful. 3. Make another film stressing the assumed formula for success. 4. Check box-office information on the new film and reassess the success formula accordingly. 5. Use the revised formula as a basis for another film. 6. Continue the process indefinitely." Although this "Game" includes the word "formula" as one of its main principles, it is definitely not a rigid set of "rules" - quite the contrary, it is a highly flexible mechanism which in based, on the one hand, on the constant reference to box-office results (i.e. profitability), and, on the other hand, on a continuous (re)assessment of the features that make a successful film. Far from creating a set of "rules" for a genre, it stresses the qualities of "repetition and variation" which we have already discussed. In a way, this process, which never stops but is closely linked to the constant evolution of the markets, is a very creative one, because it must ensure that a careful balance is achieved between the new and the old, the risks and the guarantee of success - in sum, there is no standardization without innovation - and viceversa. The history of cinema abounds in examples of the practice of the "Producer's Game". Even outside Hollywood, the game has been used time and time again: in the 1950s and 1960s, for example, the British company Hammer specialised in the production of science-fiction and horror films after the great success of "test films" like The Quatermass experiment and The curse of Frankenstein, respectively (watch the videos below). After establishing these genres, the company was able to standardize production by employing the same directors, cinematographers, set designers, and, of course, actors (like Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee) - a "recipe" which greatly helped to keep costs at the lowest possible level while maximizing profits. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

L'astronave atomica del Dottor Quatermass/The Quatermass experiment (di/by Val Guest, GB 1955) |

La maschera di Frankenstein/The curse of Frankenstein (di/by Terence Fisher, GB 1957) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sebbene i generi possano aiutare molto un'azienda a stabilire un gruppo

standardizzato di film, che vengono poi sfruttati al massimo delle

opportunità che offrono, l'industria deve stare molto attenta a

mantenere l'immagine e lo status della sua produzione

abbastanza distinguibile dai concorrenti. Ecco perché, una volta

stabilito un genere e dopo che diversi studi hanno provato a "copiare"

gli originali, un'etichetta generica può diventare inutile e persino

pericolosa per l'azienda che l'ha commercializzata per prima. Piuttosto

che descrivere i suoi film come "fantascienza" o "horror", quella

compagnia potrebbe preferire mettere in mostra ciò che ha da offrire in

termini di differenze rispetto ai suoi concorrenti, in primis

le sue star, ma anche i suoi personaggi, i suoi registi, i suoi

possibili "cicli", e così via. Un altro motivo per non essere limitati

dalle etichette generiche nella commercializzazione dei film è la

volontà di un'azienda di promuovere lo stesso film con il più vasto

pubblico possibile, e non solo i fan di un particolare genere.

Questo è un potente esempio dei diversi discorsi che contribuiscono a

formare le "etichette" assegnate a un film: non è solo una questione di

produzione (cioè quale genere una società dovrebbe assegnare a un

determinato film), ma anche, nello stesso tempo, delle strategie di

marketing e pubblicità e, non ultimo, di quale genere il pubblico

percepisce come più consono al film. Dopotutto, le aziende si preoccupano non tanto di produrre film che possano adattarsi a qualsiasi genere particolare, ma prima di tutto di sfruttare appieno il loro marchio peculiare e tutto ciò che questo ha da offrire al mercato. Questo è anche uno dei motivi per cui l'attribuzione del genere può cambiare nel tempo in risposta al mutare delle circostanze. Il primo film di James Bond, che oggi non avremmo difficoltà ad attribuire al genere "spy story", non fu affatto descritto così quando fu stato lanciato per la prima volta. Agente 007, Licenza di uccidere (si veda il trailer in basso a sinistra), il primo film di quello che sarebbe presto diventato un ciclo di enorme successo, fu semplicemente presentato nei manifesti come "Il primo film di James Bond", con l'eroe che occupava solo una piccola parte del poster, a fianco di un numero di belle ragazze; il secondo film, A 007, dalla Russia con amore (si veda il trailer in basso a destra), fu presentato in modo simile come "James Bond è tornato", ma una parte del poster aggiunge "Sean Connery nella parte di James Bond", più l'ormai già familiare gruppo di belle ragazze e un tocco di esotismo con una piccola immagine di Istanbul - chiaramente, lo sforzo era quello di stabilire un personaggio per dar vita a un ciclo, e anche, dopo il grande successo del primo film, di legare indissolubilmente il personaggio con l'attore (Sean Connery) che lo impersonava. Nessun accenno ai generi. |

Although genres can greatly help a company establish a standardized

group of films, which are then exploited to the full of the

opportunities they offer, the industry must be very careful in keeping

the image and "status" of its production quite distinguishable from

competitors. This is why, once a genre has been established and after

several studios have tried to "copy" the originals, a generic label can

become useless and even dangerous for the company which first marketed it.

Rather than describe its films as "science fiction" or "horror", that

company may prefer to make a prominent display of what it has to offer in

terms of differences from its competitors, first of all its stars, but

also its characters, its directors, its possible "cycles", and so

on. Another reason not to be limited by generic labels in the marketing

of films is a company's willingness to promote the same film with the largest

possible audience, and not just the fans of a particular genre. This is

a powerful example of the different discourses that help to

shape the "labels" assigned to a film: it is not just a question of

production (i.e. what genre a company is supposed to assign to a

particular film), but also, at the same time, but also of marketing

and publicity strategies, and, last but not least, what

genre the audiences perceive the film to belong to. After all, companies are concerned not so much with producing films that could fit any particular genre, but first and foremost to make full use of their peculiar brand name and all this has to offer to the market. This is also one of the reasons why genre attribution may change over time in response to changing circumstances. The first 007 James Bond film, which we nowadays would have no difficulty in assigning to the "spy story" genre, was not described like that at all when it was first launched. Dr No (watch the trailer below left), the first film in what would soon become a most successful cycle, was simply presented in posters as "The first James Bond film", with the hero occupying only a small portion of the poster, alongside with a number of beautiful girls; the second film, From Russia with love (watch the trailer below right),was similarly presented as "James Bond is back", but a portion of the poster adds "Sean Connery as James Bond", plus the (already familiar by now) glimpse of beautiful girls and a touch of exotism with a small image of Istanbul - clearly, the effort was to establish a character in order to give rise to a cycle, and also, after the huge success of the first film, to inextricably link the character with the actor (Sean Connery) impersonating it. No mention of genres at all. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Agente 007, licenza di uccidere/Dr. No (di/by Terence Young, GB 1962) |

A 007, dalla Russia con amore/From Russia with love (di/by Terence Young, GB 1963) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Non molto tempo dopo, sulla scia del successo di 007, fu lanciato un altro eroe/spia: Harry Palmer (interpretato da Michael Caine) che, per molti versi, potrebbe essere considerato l'antitesi di Bond: una sorta di alternativa "al ribasso", con gli occhiali e un squallido impermeabile. Eppure, se osserviamo una delle locandine che pubblicizzano il primo film del ciclo (Ipcress - si veda il trailer qui sotto), scopriamo che è descritto come "La più audace storia di "sexspionaggio" che si sia mai vista": il fatto che "sexpionage" sia scritto tra virgolette è chiaramente un segno che si stava coniando un nuovo termine, forse un nuovo genere (anche se non si è poi rivelato tale), con un accenno sia alla "spia" che alla componente sessuale della storia, che erano già affermate come marchi di fabbrica delle avventure di James Bond. In un altro poster per lo stesso film, la componente "sesso" è completamente persa e il film è descritto come "Il Goldfinger di un uomo pensante, di gran lunga più divertente di qualsiasi film di Bond e anche più gratificante!" e anche come "Un thriller ammirevole sotto ogni aspetto!". Chiaramente, la concorrenza stava cercando di sfruttare il confronto con il personaggio di James Bond, già di grande successo, e lo faceva confrontando direttamente i nomi delle due spie (con Harry Palmer descritto come un "uomo pensante", con l'ovvia implicazione che 007 non lo fosse...). La parola "thriller" è menzionata, ma non come un pesante riferimento a un genere. Ciò dimostra che in molti casi i film vengono commercializzati con il chiaro intento di fornire qualcosa di nuovo, alcune caratteristiche distinguibili, evitando così etichette "generiche" (come "spy story"), che eventualmente possono essere aggiunte (molto) dopo. |

Not much later, in the wake of 007's success, another spy-hero was

launched: Harry Palmer (played by Michael Caine) who, in many ways,

could be considered the antithesis of Bond: a sort of downbeat

alternative, wearing glasses and a dreary raincoat. And yet, if we look

at one of the

posters advertising the first film in the cycle (The Ipcress file -

watch the trailer below),

we find that it is described as "The most daring "sexpionage" story you

will ever see": the fact that "sexpionage" is printed in inverted commas

is clearly a sign that a new term was being coined, possibly a new genre

(although it didn't turn out to be so), with a hint at both the "spy"

and the "sex" components of the story, which were already established as

trademarks of the James Bond adventures. In

another poster for the same film, the "sex" component is entirely

lost, and the films is described as "A thinking man's Goldfinger,

funnier by far than any of the Bond films and more rewarding, too!" and

also as "An admirable thriller in every respect!". Clearly, the

competition was trying to take advantage of the comparison with the

already hugely successful James Bond character, and it did so by

directly comparing the names of the two spies (with Harry Palmer

described as a "thinking man", with the obvious implication that 007 was

not ...). The word "thriller" is mentioned, but not as a heavy reference

to a genre. This shows that in many cases films are marketed with the

clear intent of providing something new, some distinguishable features,

thus avoiding "generic" labels" (like "spy story"), which can eventually

be added (much) later. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ipcress/The Ipcress file (di/by Sidney J. Furie, GB 1965) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Allo stesso modo, quando la saga di Indiana Jones fu lanciata per la

prima volta, il poster del film (Indiana Jones e i

predatori dell'arca perduta) mostrava il nome del personaggio a

grandi lettere nella parte superiore, con il chiaro scopo di stabilire

un nuovo ciclo piuttosto che accennare al tipo di film che veniva

presentato (non sono state utilizzate etichette generiche, certamente

non "film d'avventura"). Quindi, tutto sommato, i generi sono un'arma a

doppio taglio per le industrie cinematografiche: possono essere

utilizzati con profitto per informare il pubblico sul tipo di storia che

viene raccontata, ma possono anche diventare una "camicia di forza" con

l'effetto opposto - quindi, ancora una volta, occorre trovare un

equilibrio tra rispondere alle aspettative del pubblico e distinguere un

particolare prodotto evitando etichette generiche, differenziandolo così

dai suoi possibili concorrenti. 11.2. La funzione socio-culturale La discussione sulle funzioni che i generi svolgono nel contesto socio-culturale è stata pesantemente influenzata da preoccupazioni ideologiche. Per alcuni, i generi sono uno dei modi migliori attraverso i quali il pubblico può vedere le proprie speranze, aspirazioni, valori, credenze e atteggiamenti rispecchiati sullo schermo; per altri, sono invece un modo attraverso il quale le istituzioni (sia private che pubbliche) possono veicolare messaggi, influenzare il comportamento delle persone e mantenere lo status quo, ovvero i valori e le ideologie delle classi dominanti e i rapporti di potere prevalenti. Questo, a sua volta, indica due concetti molto diversi della funzione dei mass media nelle società moderne: uno che enfatizza il valore della produzione popolare (di massa), l'altro che vede questa produzione come alienata e repressa dal sistema sociale dominante. In ogni caso, non c'è dubbio che i generi cinematografici, come tutti gli altri artefatti culturali, non siano neutri, ma piuttosto esprimano visioni del mondo diverse, se non addirittura alternative. I generi cinematografici (come tutti gli esempi di "generi") sono caratterizzati da alcuni tratti ricorrenti, se non ripetitivi, che tendono a fornire al pubblico personaggi, storie, situazioni che possono facilmente trasformarsi in stereotipi. Ora, gli stereotipi sono visioni eccessivamente semplificate, che negano la singolarità e la differenziazione e promuovono giudizi di valore generici e facilmente formulabili - in quanto tali, si prestano facilmente a ridurre la complessità e la diversità dei fenomeni a idee semplicistiche. Il "lieto fine" di molti film (di Hollywood) è spesso citato per provare come un pubblico possa essere facilmente influenzato e "alienato" rispetto alla pura e dura realtà, suggerendo sogni e aspirazioni che difficilmente possono essere realizzati per la maggior parte dei membri del pubblico stesso nel mondo reale. Questo è stato considerato come un modo per distrarre gli spettatori dai problemi che li attendono fuori dal cinema, lontano dallo schermo - una funzione "escapista", illusoria che i film generici possono svolgere, soprattutto in momenti particolari della storia. Il genere musicale degli anni Trenta, ad esempio, che proponeva storie d'amore in un contesto sociale (solitamente) di alto livello, dove i "problemi" potevano essere risolti cantando e ballando, portando così alla felicità della coppia in questione (come nei film di Fred Astaire e Ginger Rogers), è stato visto come un potente strumento per allontanare il pubblico dalla realtà della Grande Depressione e verso un mondo immaginario e illusorio, un modo per fuggire dalla realtà quotidiana dei problemi sociali reali. Allo stesso modo, mostri appartenenti a tradizioni cinematografiche molto diverse, da Nosferatu di Murnau, realizzato nel 1922 nel difficile periodo della Repubblica tedesca di Weimar, a Dracula di Tod Browning (1931) e King Kong di Cooper e Schoedsack nei primi anni '30 della Grande Depressione americana (si vedano i video qui sotto), sembrano allontanare il pubblico dalla realtà deprimente dei tempi, spostandolo su un altro livello immaginario: "[King Kong]... converte il pericolo sociale (la crisi) in un pericolo sessuale (la rappresentazione della crisi coinvolge esclusivamente una donna - Ann è una ladra prima di diventare il catalizzatore della passione amorosa di Kong). Allo stesso tempo, svuota il tempo storico della sua cultura effettiva (New York negli anni '30) per sostituirlo con un mondo mitico e immaginario (il regno di Kong). Non sorprende che commentatori e critici abbiano spesso visto nell'irruzione di King Kong a New York il ritorno, terrificante e fantasmagorico, del rimosso – sia psichico (l'Altro, il desiderio, l'onnipotenza delle pulsioni, ecc.), sia sociale (la Grande Depressione, i cui effetti sono solo velocemente mostrati all'inizio del film, ritornando sotto forma di un mostro che distrugge tutto al suo passaggio)" (Nota 5) |

Similarly, when the Indiana Jones saga was first launched, the

poster for the film (Indiana Jones and the raiders of the lost

ark) showed the name of the character in large letters at the top of

the poster, with the clear purpose of establishing a new cycle rather

than hinting at the kind of film that was presented (no generic labels

were used, certainly not "adventure film"). So, all in all, genres are a

double-edged sword for cinema industries: they can be profitably used to

inform audiences of the kind of story being told, but they can also

become a "straightjacket" with the opposite effect - so, once again, a

balance must be struck between addressing audience expectations and

distinguishing a particular product by avoiding generic labels and thus

differentiating it from its possible competitors. 11.2. The socio-cultural function The discussion on the functions that genres fulfil in the socio-cultural context has been heavily influenced by ideological concerns. For some, genres are one of the best ways through which audiences can see their hopes, aspirations, values, beliefs and attitudes mirrored on the screen; for others, they are instead a way through which institutions (both private and public) can convey messages, influence people's behaviour and maintain the status quo, i.e. the values and ideologies of the dominant classes and the prevailing power relationships. This, in turn, points to two very different concepts of the function of mass media in modern societies - one emphasizing the value of popular (mass) production, the other seeing this production as alienated and repressed by the dominant social system. In any case, there is no doubt that film genres, as all other cultural artifacts, are not neutral, but rather express different, even alternative, world views. Film genres (like all examples of "genres") are characterized by some recurring, if not repetitive, features, which tend to provide audiences with characters, stories, situations which can easily turn into stereotypes. Now, stereotypes are over-simplified views that deny singularity and differentiation and promote generic, ready-made value judgments - as such, they lend themselves easily to reducing the complexity and diversity of phenomena to simplistic ideas. The "happy ending" of many (Hollywood) movies is often cited to show how an audience can easily be influenced and alienated from the harsh facts of reality, suggesting dreams and aspirations that can hardly be realized for most members of the audience itself in the real world. This has been considered as a way to distract viewers away from the problems that await them outside the theatre, far from the screen - an "escapist", illusionary function that generic films can fulfil, especially at particular times in history. The musical genre of the 1930s, for example, by offering love stories in a (usually) high-level social context, where "problems" can be solved by singing and dancing, leading to the bliss of the couple in question (remember the Astaire-Rogers films) has been seen as a powerful instrument to move audiences away from the realities of the Great Depression and into an imaginary, illusionary world, a way to escape from the daily reality of actual social problems. In the same vein, monsters belonging to vastly different film traditions, from Murnau's Nosferatu, made in 1922 in the critical period of the German Republic of Weimar, to Tod Browning's Dracula (1931) and Cooper and Schoedsack's King Kong in the early 1930s American Great Depression (watch the videos below), seem to transfer the audience away from the depressing reality of the times, displacing them to another, imaginary level: "[King Kong]... converts social danger (the crisis) into a sexual danger (the representation of the crisis exclusively involves a woman – Ann is a thief before becoming the catalyst for Kong’s amorous passion). At the same time, it empties historical time of its actual culture (New York in the 1930s) in order to replace it with a mythical and imaginary world (the kingdom of Kong). It is not surprising that commentators and critics have often seen in the irruption of King Kong in New York the return, terrifying and phantasmagorical, of the repressed – whether psychic (the Other, desire, the all-powerfulness of impulses, etc.), or social (the Great Depression, the effects of which are quickly shown and evacuated at the beginning of the film, returning in the form of a monster that destroys everything in its passage)" (Note 5) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Nosferatu il vampiro/Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror/ Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens (di/by Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau, Germania/Germany 1922) |

King Kong (di/by Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack, USA 1933) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Più di recente, in periodi critici simili, i generi cinematografici

hanno aiutato gli spettatori a distogliere la loro ansia dai problemi

sociali ed economici reali spostando le loro paure su cause alternative,

come hanno cercato di fare i cosiddetti "film catastrofici": gli anni

'70 hanno visto la produzione di film come

L'avventura del Poseidon (di Ronald Neame, USA 1972),

L'inferno di cristallo (si veda il trailer in basso a

sinistra) e persino il primo blockbuster di Spielberg,

Lo squalo

(USA 1975) - ma gli anni '70 sono stati anche il periodo che ha visto la

guerra del Vietnam, lo scandalo Watergate, la crisi petrolifera e la

recessione economica. Chi credeva nella funzione alienante dei generi

cinematografici aveva motivo di suggerire che i pericoli reali fossero

sostituiti ed esorcizzati da pericoli fittizi e lontanissimi,

rafforzando così l'ideologia dei valori sociali dominanti. Whright (Nota 6) si spinge fino a suggerire che alcuni dei generi cinematografici più popolari (in particolare a Hollywood) assolvono tutti a questa funzione, presentando una visione semplificata della realtà dove i problemi vengono risolti in modo superficiale in modo da lasciare il pubblico "esorcizzato " e soddisfatto di quello che è solo un altro modo per voltare le spalle ai problemi "veri". Così i film di fantascienza traducono i problemi posti dall'"Altro" in forze aliene; i western mostrano come la violenza possa portare all'uso della forza per raggiungere l'ordine legale; e i film di gangster dimostrano che il "gangster", cioè un fuorilegge che cerca di salire la scala sociale con la violenza, è in definitiva un eroe tragico, destinato al fallimento e forse alla morte, poiché il successo cercato al di fuori della propria classe sociale non porta alcuna ricompensa. Questa visione ideologica viene nascosta sostituendo le reali cause sociali di questa condizione umana con cause psicologiche, tanto che la tragica figura del gangster viene spesso presentata come una personalità psicotica (come in Nemico pubblico - si veda il trailer in basso a destra). |

More recently, in similar critical periods film genres have helped

viewers divert their anxiety from actual social and economic problems by

displacing their fears to alternative causes, as the so-called disaster

movies tried to do: the 1970s saw the production of films like

The

Poseidon adventure

(by Ronald Neame, USA 1972),

The towering inferno (watch the trailer below left) and even the early Spielberg blockbuster

Jaws (USA 1975) -

but the 1970s were also the time that saw the Vietnam War, the Watergate

scandal, the oil crisis and an economic recession. Those who believe

in the alienating function of film genres had reasons to suggest that

real dangers were replaced and exorcised by fictitious, far-removed

dangers, thus reinforcing the ideology of the dominant social values. Whright (Note 6) goes so far as to suggest that some of the most popular (Hollywood) film genres all fulfil this function, by presenting a simplified view of reality where problems are solved in a superficial way so as to leave the audience "exorcised" and satisfied with what is just another way of turning one's back to the "real" problems. Thus science-fiction films dissolve the problems posed by "the Other" into alien forces; westerns show how violence can lead to the use of force to achieve legal order; and gangster films demonstrate that the "gangster", i.e. an outlaw who tries to climb the social ladder with violence, is ultimately a tragic hero, destined to failure and possibly death, since success sought outside one's own social class brings no reward. This ideological view is hidden by replacing the real social causes of this human condition with psychological causes, so that the gangster's tragic figure is often presented as a psychotic personality (as in The public enemy - watch the trailer below right). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

L'inferno di cristallo/The towering inferno (di/by John Guillermin, Irwin Allen, USA 1974) |

Nemico pubblico/The public enemy (di/by William A. Wellman, USA 1931) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Tuttavia, questa visione "negativa" della funzione sociale dei generi

cinematografici è controbilanciata da altri approcci, che tendono a

presentarli come espressioni collettive dei contesti socio-culturali e

dei problemi dei rispettivi pubblici - in questo caso, il genere non è

visto come una manipolazione degli spettatori, ma piuttosto come un

potente modo per evidenziare tensioni e conflitti nel tentativo di

esprimerli sullo schermo e possibilmente anche risolverli. Secondo

questa visione, quindi, i western incarnano, attraverso le loro storie e

personaggi, alcuni conflitti culturali essenziali (ad esempio il mito

della frontiera come linea di demarcazione tra deserto e civiltà), che

già esistono come concetti appartenenti alla struttura mentale di una

società. Schatz (Nota 5) suggerisce che la maggior parte dei generi

cinematografici classici esprimono una delle due grandi classi di

conflitti attraverso le loro strutture narrative e le relative

iconografie: da un lato, il western, il poliziesco e il film di gangster

danno concretezza al già citato conflitto tra il legale e l'illegale, il

caos e l'ordine, e sono quindi piuttosto "fisici" nella loro messa in

scena che privilegia gli spazi aperti; il musical, la commedia

"screwball" e il melodramma, invece, esprimono conflitti psicologici più

personali attraverso una messa in scena che predilige gli spazi

"chiusi". Naturalmente, un'opposizione così drastica deve essere

mitigata evitando semplici dicotomie (ad esempio non tutti i film del

primo tipo mettono degli uomini in evidenza, e non tutti i film del

secondo tipo mettono le donne in evidenza) - oltre al fatto che, come

abbiamo già menzionato, i generi spesso si mescolano e le distinzioni

nette non possono essere fatte così facilmente. L'ultima parte del secolo scorso, e sempre di più il 21° secolo, hanno visto un enorme sviluppo di quelli che possono essere generalmente classificati come "film fantasy" - una sorta di super-genere che in realtà attraversa diversi generi più tradizionali come la fantascienza e l'horror, oltre alla straordinaria produzione di film di supereroi. La preoccupazione centrale di tutti questi film sembra essere un conflitto, o almeno un confronto, tra "l'uomo" e "altri esseri", come creature non umane, semi-umane e persino animali. È l'identità umana che è qui chiaramente in gioco: l'impossibilità dell'uomo moderno di definire se stesso e la sua natura, di fronte a "macchine" che non possono essere semplicemente "utilizzate" ma lasciano il posto a diversi tipi di relazioni (positive e negative), con una dimensione virtuale che sembra sempre più connotare tali relazioni. Così i film "fantasy", nella loro ricca gamma di "sottogeneri", sollevano questioni di identità, inclusione ed esclusione, forze positive e negative in gioco tra l'uomo e un mondo che sta rapidamente cambiando i suoi connotati tradizionali. A partire da James Bond, che “usa” in modo magistrale macchine e tecnologia senza dimenticare la sua sensualità (di cui è anche maestro), e proseguendo con le saghe di Star Wars e Star Trek, dove androidi e umani si interfacciano e sono agenti attivi nella lotta tra il bene e il male, tra le forze della "vita" e quelle della "morte", i film "fantasy" hanno anche avuto a che fare con extraterrestri malvagi che si infiltrano persino nel corpo umano (come nel franchise di Alien - si veda il video qui sotto), e, anche se in modi del tutto diversi, con gli animali come un'altra dimensione della vita umana e le biotecnologie associate (da Jaws a Jurassic Park), fino a raggiungere la dimensione ultra o soprannaturale di generazioni di supereroi. |

However, this "negative" view of the social function of film genres is

counterbalanced by other approaches, which tend to present them as

collective expressions of the socio-cultural contexts and problems of

their respective audiences - in this case, the genre is not seen as a

manipulation of the viewers but rather as one powerful way of

highlighting tensions and conflicts in an attempt to express them on the

screen and possibly even solve them. According to this view, then,

westerns embody, through their stories and characters, some essential

cultural conflicts (e.g. the myth of the frontier as the dividing line

between wilderness and civilization), which already exist as concepts

belonging to a society's mental structure. Schatz (Note 5) suggests that

most classical film genres express one of two major classes of conflicts

through their narrative structures and their corresponding

iconographies: on the one hand, the western, the detective film and the

gangster film give concrete substance to the already mentioned conflict

between the legal and the illegal, chaos and order, and are thus quite

"physical" in their mise-en-scène which privileges open spaces; on the

other hand, the musical, the screwball comedy and the melodrama express

more personal psychological conflicts through a mise-e-scène that

prefers "enclosed" spaces. Of course, such a drastic opposition needs to

be tempered by avoiding simple dichotomies (e.g. not all movies of the

first class feature men prominently, and not all films of the second

class feature women prominently) - plus the fact that, as we have

already mentioned, genres often mix and clear-cut distinctions cannot

so easily be made. The latter part of last century, and increasingly the 21st century, have witnessed a huge development of what may generally be classed "fantasy films" - a sort of super-genre which actually cuts across several different, more traditional genres like science-fiction and horror, plus the amazing production of super-hero films. The central concern of all these films seems to be a conflict, or at least a confrontation, between "man" and "other beings", like non-human, semi-human and even animal creatures. It is human identity which is clearly at stake here: modern (wo)man's impossibility to define her/himself and her/his nature, when faced with "machines" which cannot simply be "used" but give way to different sort of (positive and negative) relationships, with a virtual dimension which increasingly seems to connote such relationships. Thus "fantasy" films, in their rich range of "sub-genres", raise questions of identity, inclusion and exclusion, positive and negative forces at play between man and a world that is rapidly changing its traditional connotations. Starting with James Bond, who "uses" machines and technology in a masterly way while not forgetting his sensuality (of which he is a master, too), and proceeding with the Star Wars and Star Trek sagas, where androids and humans interface and are active agents in the struggle between good and evil, "life" and "death" forces, "fantasy" films have also dealt with evil extra-terrestrials who even infiltrate the human body (as in the Alien franchise - watch the video below), and, although in quite different ways, with animals as another dimension of human life and the associated biotechnologies (from Jaws to Jurassic Park), until we reach the ultra- or super-natural dimension of generations of super-heroes. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

La saga di Alien/The Alien saga |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

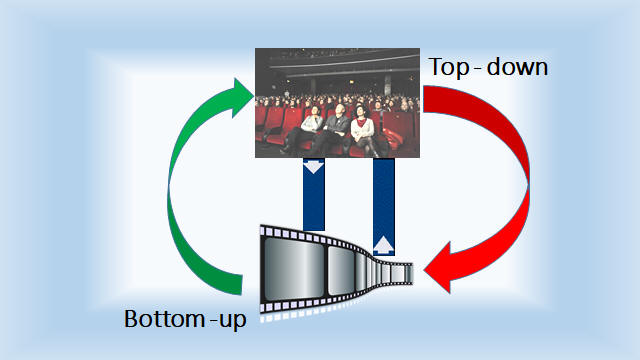

Queste considerazioni ci aiutano anche a comprendere il potenziale dei

generi cinematografici come agenti socio-culturali. Il consumo di film

di genere, spesso (sebbene oggi sicuramente meno che in passato) svolto

come esperienza collettiva, fornisce non solo il piacere di vedere sullo

schermo l'espressione dei propri valori e/o conflitti, ma anche

l'opportunità di vivere l'esperienza della condivisione di

preoccupazioni comuni, di sentire (anche se forse brevemente e

fugacemente) un senso di "comunità". Naturalmente, come abbiamo appena

visto, questa visione dei generi cinematografici è sempre filtrata da

ideologie contrapposte. Allo stesso tempo, però, le funzioni socio-culturali dei generi cinematografici, come li abbiamo considerati in questa sezione, devono prestare la dovuta attenzione al ruolo del pubblico, poiché i film acquisiscono il loro pieno significato quando vengono effettivamente visti, analizzati e interpretati da spettatori reali, che non sono solo destinatari passivi di suoni e immagini dallo schermo. Le esperienze degli spettatori con i film precedenti, le loro motivazioni, aspettative, credenze e atteggiamenti interagiscono con i film come testi, rendendo il pubblico parte attiva del processo, iper cui le funzioni dei generi possono essere valutate solo alla luce di questa interazione. Inoltre, la stragrande maggioranza degli studi sui generi cinematografici riguarda i film di Hollywood, insinuando così il dubbio di una visione etnocentrica. Altre industrie cinematografiche, che sono l'espressione di culture diverse, producono generi cinematografici che possono essere interpretati in modo molto diverso. Certamente le industrie cinematografiche di Hollywood (e, almeno in parte, più in generale occidentali) sono potenti società finanziarie, ovviamente al servizio dell'interesse economico e ideologico dei loro stakeholder, il che rende i loro prodotti (film e generi cinematografici in particolare) in grado di esercitare un certo grado di controllo anche sul lato ricettivo, cioè sul pubblico. Questa è una chiave cruciale per spiegare il successo di un genere hollywoodiano, mettendo così in relazione le funzioni economiche con le funzioni socio-culturali dei generi. La formula, come ha mostrato Altman (Nota 7) è quella di coniugare gli obiettivi economico-finanziari dell'industria cinematografica con le aspirazioni e le preferenze del pubblico: quando ciò accade, il successo al botteghino è (quasi) assicurato, e le implicazioni ideologiche dell'intera operazione di solito rimangono in secondo piano. Il pubblico può continuare a godere di piaceri che altrimenti non sarebbero consentiti facendone esperienza attraverso i filtri dei film di genere: così, gangster, mostri orribili e alieni pericolosi possono compiere ogni sorta di azioni orribili sullo schermo, con la certezza che alla fine saranno puniti; e i personaggi delle commedie possono spingersi un po' troppo oltre nei loro incontri e incomprensioni sessuali, con la certezza che il comportamento "corretto" verrà ripristinato entro la fine del film. 11.3. La funzione comunicativa Il livello di comunicazione primario supportato dai generi cinematografici è ovviamente rispetto al pubblico, che è il consumatore finale del film come prodotto. Abbiamo già notato come i generi, presentando al pubblico convenzioni ben note e accettate (da argomenti e temi a personaggi e ambientazioni, ecc.) aiutino notevolmente gli spettatori ad attivare aspettative, a recuperare conoscenze di base ed eventualmente a comprendere, interpretare e apprezzare un particolare film "generico". La risposta del pubblico è un complesso processo psicosociale (descritto in dettaglio nel Dossier Aspettative, atteggiamenti e strategie: un ponte tra schermo e pubblico), in cui gli spettatori costruiscono attivamente un significato da ciò che vedono e sentono combinando due tipi principali di processi mentali: top-down (la conoscenza e l'esperienza precedenti che apportano alla visione) e bottom-up (le informazioni fornite attraverso il testo del film che stanno guardando), come mostra la figura seguente. |

These considerations also help us to realize the potential of film

genres as socio-cultural agents. The consumption of generic films, often

(although now certainly less than in the past) carried out as a

collective experience, provides not just the pleasure of seeing one's

own values and/or conflicts expressed on the screen, but also the

opportunity to experience the sharing of common concerns, of feeling

(although maybe briefly and fleetingly) a sense of "community". Of course, as we

have just seen, this view of film genres is always filtered through

opposing ideologies. At the same time, however, the socio-cultural functions of film genres, as we have considered them in this section, must give due attention to the role of audiences, since films acquire their full meaning when they are actually seen, analysed and interpreted by actual viewers, who are not just passive recipients of sounds and images from the screen. Viewers' experiences with previous films, their motivations, expectations, beliefs and attitudes interact with the films as texts, making audiences active participants in the process, so that the functions of genres can only be assessed in the light of this interaction. Also, the vast majority of studies on film genres deal with Hollywood movies, thereby insinuating the doubt of an ethnocentric view. Other film industries, which are the expression of different cultures, produce film genres that may be interpreted quite differently. Certainly the Hollywood (and, at least partially, more generally Western) cinema industries are powerful financial corporations, obviously serving the economic and ideological interest of their stakeholders, which makes their products (films, and film genres in particular) capable of exercising a degree of control on the receptive side as well, i.e. on audiences. This is a crucial key in explaining the success of a Hollywood genre, by relating the economic with the socio-cultural functions of genres. The formula, as Altman has shown (Note 7) is to combine the financial-economic objectives of the cinema industry with the aspirations and preferences of audiences: when this happens, box-office success is (almost) assured, and the ideological implications of the whole operation usually remain in the background. Audiences can continue to delight in pleasures that would otherwise not be allowed by watching them through the filters of genre films: thus, gangsters, horrific monsters and dangerous aliens can commit all sorts of hideous actions on the screen, with the assurance that by the end they will be punished; and characters in comedies can go a little too far in their sexual encounters and misunderstandings, with the assurance that "proper" behaviour will be restored by the end of the movie. 11.3. The communicative function The primary level of communication supported by film genres is obviously with respect to the audiences, who are the final consumers of film as product. We have already remarked how genres, by presenting audiences with well-known, accepted conventions (from topics and themes to characters and settings, etc.) greatly help viewers to activate expectations, to retrieve background knowledge and eventually to understand, interpret and appreciate a particular "generic" film. Audience response is a complex psycho-social process (described in detail in the Dossier Expectations, attitudes and strategies: a bridge between screen and audience), whereby viewers actively construct meaning from what they see and hear by combining two main kinds of mental processes: top-down (the previous knowledge and experience which they bring to the viewing) and bottom-up (the information that is delivered through the actual film text they are viewing), as the figure below shows. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Il ruolo che i generi giocano in questo processo difficilmente può essere sottovalutato. Mettendo a disposizione contenuti convenzionali ben noti, aiutano il pubblico ad avvicinarsi a un film con l'anticipazione cognitiva e il coinvolgimento emotivo corretti e appropriati, il che rende il processo di formazione del significato più facile e veloce. Non appena guardiamo la sequenza di apertura di un qualsiasi film di James Bond (si veda il video qui sotto) attiviamo subito una serie di elementi informativi, molti dei quali sono convenzioni che abbiamo imparato guardando i precedenti film di 007 (dai temi ai personaggi, dalle tipiche situazioni fino ai minimi dettagli della vita e dei tratti caratteristici di James Bond). |

The role that genres play in this process can hardly be

underestimated. By making available well-known conventional content,

they assist audiences in approaching a film with the correct and

appropriate cognitive anticipation and emotional

involvement, which makes the process of meaning-formation easier and

quicker. As soon as we watch the opening sequence of any James Bond film

(watch the video below) we immediately activate a range of information

elements, many of which are conventions that we have learned by

watching previous 007 movies (from themes to characters, from typical

situations to the smallest details about James Bond's life and

characteristic features). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Un collage delle sequenze di apertura dei film di James Bond (1962-2006)/A collage of James Bond films opening sequences (1962-2006) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Questa potente funzione che i generi esercitano sul pubblico è stata considerata, da un lato, in termini di linee guida utili che aiutano e migliorano la comprensione e l'apprezzamento di un film da parte degli spettatori, e, dall'altro, in termini di percorsi prestabiliti che gli spettatori sono obbligati a seguire, limitando in qualche modo la propria esperienza personale con il film stesso e suggerendo significati "preferiti". Entrambe le posizioni hanno del vero, ma non riescono a riconoscere che il pubblico è composto da individui che hanno una propria "storia" in termini di esperienze e aspettative precedenti, e anche che più utenti possono dare origine a molteplici (e spesso contrastanti) interpretazioni . In altre parole, gli spettatori non sono soggetti passivi, ma piuttosto attivi "costruttori" di significato, per cui guardare un film è un processo continuo, in cui le convenzioni di genere giocano il loro ruolo nel contesto di una mente attiva, che è anche vigile nell'individuare deviazioni dalle convenzioni e nel rispondere a colpi di scena inaspettati. Perché un film abbia successo, almeno al botteghino, deve esserci una sorta di tacito, implicito accordo tra il film (e i suoi realizzatori) e il pubblico, che deve accettare alcune essenziali caratteristiche condivise (le " convenzioni del genere") ma deve anche sentirsi libero di orientare la propria visione secondo le proprie esperienze, credenze, atteggiamenti e valori. In altre parole, guardare un film non è "accettare" o "rifiutare" la sua forma e il suo contenuto, ma è piuttosto una questione di "negoziare" tra diverse interpretazioni, e persino di discuterle o rifiutarle. Ciò si ricollega anche all'osservazione che abbiamo già fatto, ovvero che lavorare all'interno di un genere significa non solo avvalersi di convenzioni consolidate ("ripetizione") ma anche inventare qualcosa di nuovo e magari inaspettato ("variazione") (si veda la Prima parte). Troppa routine diventa noiosa, ma troppe sfide possono portare all'irritazione del pubblico, a incomprensioni e, in casi estremi, al sovvertimento del genere, che perde così il suo valore e la sua utilità. |

This powerful function that genres exercise over audiences has been

considered, on the one hand, in terms of useful guidelines which assist

and improve viewers' understanding and appreciation of a movie, and, on

the other hand, in terms of pre-determined routes that viewers are

obliged to follow, in a way limiting their own personal experience with

the movie itself and pointing to "preferred" meanings. Both positions

have some truth in them, but fail to recognize that audiences are made

up of individuals who have their own "story" in terms of previous

experiences and expectations, and also that multiple users can give rise

to multiple (and often conflicting) interpretations. In other words,

audiences are not passive subjects, but rather active "constructors" of

meaning, so that watching a movie is an on-going process, in which genre

conventions play their role within the context of an active mind who is

also alert in spotting deviations from the conventions and in responding

to unexpected twists and turns. In order for a movie to be successful,

at least at the box-office, there must be a sort of tacit, implicit,

agreement between the film (and its makers) and the audiences, who must

accept some essential shared features (the "conventions of the genre")

but must also feel free to orient their viewing according to their own

experiences, beliefs, attitudes and values. In other words, watching a

movie is not a matter of "accepting" or "refusing" its form and content,

but is rather a matter of "negotiating" between different

interpretations, and even of debating or rejecting them. This also

relates to the remark we have already made, i.e. that working within a

genre means not only making use of well-established conventions

("repetition") but also inventing something new and perhaps unexpected

("variation")(see Part 1). Too much routine gets boring,

but too many challenges may lead to the audience's irritation,

misunderstanding and, in extreme cases, to the genre being subverted,

thus losing its value and usefulness. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

UN MOMENTO PER RIFLETTERE

UN MOMENTO PER RIFLETTEREIl potere delle convenzioni di genere diventa particolarmente evidente quando vengono "violate", cioè quando formiamo aspettative sulla base delle convenzioni, ma poi siamo costretti a "riorientarle" alla luce di nuovi input, o di nuovi elementi che compaiono sul schermo. * Guarda i primi 60 secondi del Video 1 qui sotto e poi ... STOP. A quale genere pensi appartenga questo film? Elenca brevemente le convenzioni che ti aiutano a formare aspettative sul genere coinvolto. * Ora continua a guardare il video. Le tue aspettative sono cambiate? Perché, cioè quali nuovi elementi vengono introdotti e sfidano la tua attribuzione iniziale del film a un genere particolare? * Guarda il Video 2 qui sotto. Ancora una volta, decidi a quale genere pensi appartenga il film e fai un breve elenco delle convenzioni pertinenti. * In entrambi i casi (Video 1 e Video 2) in che modo la tua precedente conoscenza del film, del regista, degli attori, ecc. ti ha aiutato a formare le tue aspettative riguardo al genere coinvolto? |

STOP AND THINK