What's a "good" film? A few answers to an impossible question

Part 3: Mental mechanisms behind value attribution

Luciano Mariani

info@cinemafocus.eu

© 2025 by Luciano

Mariani, licensed under CC

BY-NC-SA 4.0

|

1. Introduction In this third part we will move from considering the criteria by which a film can be defined, at least by some viewers, as a “good” film, to examining the mental mechanisms that come into play in this process of value attribution, i.e. what operations a viewer performs in order to “love” a film. Our starting point is the observation that human beings naturally tend to wonder about the causes of phenomena that attract their attention. When faced with certain experiences (e.g., seeing ivy twining around a tree trunk or a sudden change in the movement of the sea), we do not normally ask ourselves what the reason is behind what we see (we know that it is nature and its laws), even if rarer phenomena, which are not part of everyday experience and whose precise reasons are unknown (e.g., a volcanic eruption), may stimulate curiosity more than others, especially if we do not have the relevant knowledge. But this search for causality becomes much more pressing in social interactions, when everyday communication, which is the basis of our community life, can pose problems and thus stimulate reflection. As social beings, we are normally very sensitive, even if unconsciously, to the communicative acts in which we are involved. The signals we receive from others, through verbal language (words) and through non-verbal language (gestures, looks, smiles ...) are constantly interpreted in order to provide the most appropriate responses, but if something does not work, for example if these signals are ambiguous or unexpected, we immediately wonder what prompted our interlocutor to emit that signal - the search for the cause of this episode is driven by the premise, which we take for granted, that behind every communicative act there is an intention on the part of its sender. If someone asks me the time in front of a wall where a large clock hangs, or if a stranger stares intently into my eyes, the perception of these communicative acts (verbal or non-verbal) triggers in me the need to understand what caused them. In other words, stimuli from others are normally considered intentional, i.e. the result of conscious choices on the part of our interlocutors: I can then hypothesise, for example, that the person asking me the time does not trust the clock on the wall or the one on their wrist, and that the person staring at me has recognised someone familiar in me... 2. Film as an intentional stimulus Similarly, during and after watching a film, viewers constantly ask themselves, albeit usually completely unconsciously, what the filmmakers (not only the director, but all the other figures involved in this collective endeavour, such as the screenwriter, the director of photography, the editor, the score composer, and so on) are trying to say. This is particularly true if what we see and hear surprises or perplexes us because it is unusual, ambiguous, incomprehensible or even simply contrary to our expectations. In other words, we attribute a specific intention to the film (or rather, to its creator), which becomes all the more salient the more we are unable to immediately grasp its precise meaning. An image, a sound, a noise or a musical motif can thus mobilise our attention to try to interpret the underlying causes and at least hypothesise what goals, beliefs, attitudes, motivations, personality traits, or, to use a very general term, mental states led the filmmaker (the director or whoever else) to make the choices they made. In particular, when faced with ambiguous stimuli, we ask ourselves what the film wants us to understand, feel, judge ... what cognitive and emotional reactions it expects us to set in motion. In these cases, our attention becomes more conscious and, in a sense, we “distance” ourselves from the film in order to better interpret the stimulus (which we perceive as intentional) that is offered to us. Of course, our everyday reality differs from that of cinema: even if a film claims to be realistic, i.e. to reflect reality, it is in fact the result of a selection and organisation of scenes, characters, behaviours ... usually carefully “manipulated” (in the positive or at least neutral sense of the word), based on cinematic conventions that we accept in a film but would not accept in real life. Not only do shots, scenes or sequences constantly move us through space and time, but they can also, unlike in everyday experiences, add other, alternative dimensions to what we see and hear: a scene can thus become allusive, ironic, symbolic ... There is no doubt that cinematic conventions such as editing or camera movements are linked to the ways in which we deal with and interpret real life, but at the same time they transcend everyday reality because they are used to serve an alternative, intentionally constructed reality, such as that of a film. Even a single object can take on a meaning and significance that go beyond its simple physical perception: in The Kite Runner, we see the two young protagonists (Amir, a wealthy, motherless Afghan boy from Kabul, and his friend Hassan, son of the poor servant of Amir's family) playing at “hunting” kites, i.e. trying to cut the string of their opponent's kite - the two boys are so good at it that they become champions of Kabul. The sight of kites immediately triggers possible experiences, memories and regrets in viewers (which naturally vary depending on the “baggage” that each viewer carries with her/him, but, when placed in a family, social and cultural context so distant from Western eyes, we may also ask ourselves (even unconsciously) what meaning they will take on in the film, what role they will play, whether they will, for example, advance the story or enrich the description of the characters or whether, on the contrary, they will be treated as mere props - and the answers we give to these questions will also determine how we perceive and remember these kites (and therefore the role they will play in our interpretation of the film). At the same time, the context of the two boys, who are friends but so different in terms of social background, may also make us perceive, in the course of the film, that kites can become a symbol of freedom and liberation from heavy social and cultural constraints. |

|

|

The kite runner (Marc Foster, USA 2007) |

|

|

Our perception of what we see and hear coming from the screen is therefore based on our general ability to interpret our daily experiences, but the film, through its own devices, leads us to transcend the simple direct recognition of objects, characters and situations, prompting us to ask further questions about what the film itself intends to communicate through the introduction and organisation of these elements. When Hitchcock, in Vertigo, shows us the woman (Kim Novak) whom the detective (James Stewart) is following, entering a museum and sitting in front of a painting, then staring at the character depicted in the painting for a long time, he directs our attention to the woman's hair (A) and then immediately afterwards to that of the woman in the painting (B), which is styled in the same way. In this way, the hairstyle immediately takes on a meaning that transcends the mere physical fact to suggest a much more intriguing link between these two female figures. And the most attentive viewers (or even those who watch the film two or more times) will notice that Hitchcock uses the “spiral” motif (present in the hairstyle) as a recurring element in the film, starting with the opening credits (C), in which the detective has a nightmare in which he seems to fall into a vortex that swallows him up, to the spiral staircase of the monastery tower (D) where two crucial scenes take place. |

|

|

|

|

A

B

C

D Vertigo (Alfred Hitchcock, USA 1958) |

|

|

To give another example, when Eisenstein, in the aforementioned Battleship Potemkin, wants us to understand the reasons for the mutiny, he uses a montage of scenes among the sailors, placed in rapid succession with images of worms infesting the meat intended for meals (at 05:39): this montage not only informs us about hygiene on board the ship, but also dramatically illuminates the conditions in which the sailors are kept and, more broadly, the rebellion against a violent and oppressive system. The juxtaposition of scenes is the device the director uses to “make the images speak”, enriching them with a symbolic meaning that transcends the pure representation of objects. Once again, we make sense of what we see because, more or less consciously, we ask ourselves what intentions motivated the director in his choices of content and form: we enter his state of mind in order to interpret what we see. And, at least to a certain extent, we share with him/her the knowledge of the cinematic conventions used in the film: even if it is the first time we have seen this scene, and even if we are not film buffs, we understand that the fast editing is telling us something - something that goes beyond the images themselves. |

|

|

Бронено́сец «Потёмкин»/Battleship Potemkin (Sergej Michajlovič Ėjzenštejn, URSS 1925) |

|

|

3. Attributing intentions to the director: from classic cinema to (post)modern cinema Films certainly vary greatly in terms of the possibility for viewers to attribute intentions to the director. For example, “classical Hollywood” films (roughly at its peak between the 1940s and 1960s) were designed to offer the audience a linear and easily understandable story, with characters motivated by specific choices and, consequently, with a clear chain of cause and effect that translated into logically connected events, from the beginning to the often inevitable happy ending. A film produced with this type of device was therefore easy to understand and interpret, and all cinematic conventions served this basic function. But it was equally important that the devices (from the shots to the camera movements, from the editing to the soundtrack, and so on) remained hidden, so to speak, from the eyes of the viewers, in order to give the illusion that the film “proceeded on its own” and resulted in a fluid, always clearly understandable viewing experience. In this production system, the audience did not feel the need (nor did they have the opportunity) to question the director's intentions, who, like all the professionals involved, was thus “invisible”. Of course, this did not prevent the directors themselves, especially those with "authorial" ambitions, to include moments and images in their films that could somehow stimulate viewers (perhaps not all of them) to pause and wonder about the meaning of what they were seeing and hearing: we have just seen how "classical" directors, as different as Hitchcock and Eisenstein, managed to "leave their mark" through sophisticated images with multiple and sometimes very complex meanings. With the advent of “modern” cinema, coinciding with the so-called “New Hollywood” and the “new waves” (nouvelle vagues) of many new national film industries, the classical model was quickly thrown into crisis: faced with changing social and cultural scenarios, the new cinema responded with a renewal not only of content but also of form, with directors now often more inclined to “reveal” the hidden and implicit mechanisms of classical cinema, while at the same time taking on the role of “authors” more radically. In this way, viewers were also encouraged to take a more active and conscious approach to films and, at the same time, to take responsibility for asking themselves what the director's intentions were when faced with complex images. Even in this case, however, the film landscape remained varied and certainly not standardised or flattened into a few models. With subsequent “post-modern” developments, starting in the 1980s, cinema has further evolved towards forms of expression that challenge classical genres, sometimes re-inventing them in original ways, revisiting themes and forms of expression from the past, with a greater awareness of the “mechanisms of cinema” themselves. This has generally led to a different relationship with viewers, who are now more aware of what cinema has been able to offer and still offers, and therefore more willing to interpret the intentions of directors in their choice and treatment of content (stories, characters, events, etc.) and forms (styles, "film language", etc.) that are complex and often layered, beyond or beneath the surface of images and sounds. |

|

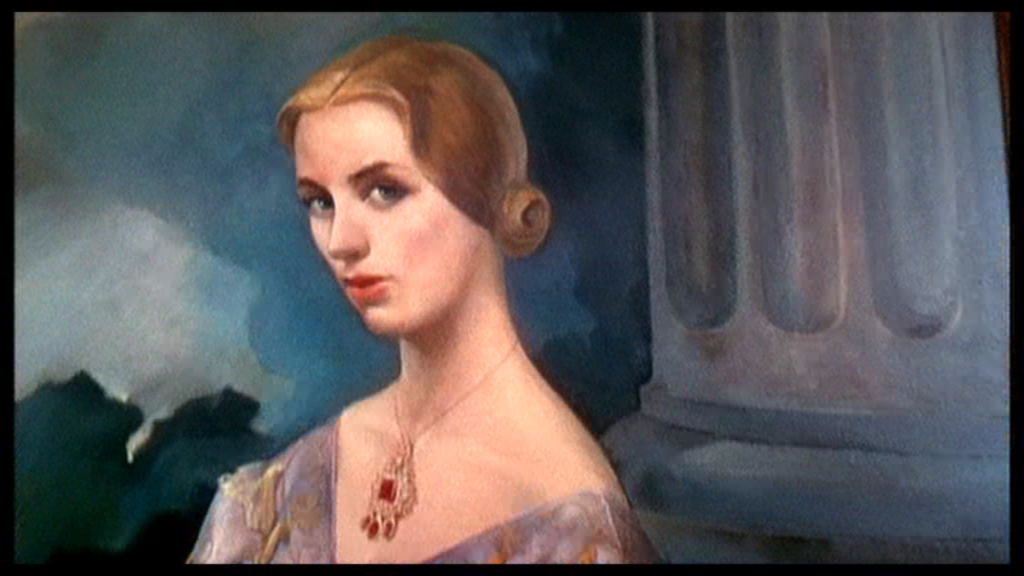

Both Barry Lyndon (Stanley Kubrick, UK-US 1975) and The Story of My Wife/A feleségem története (Ildikó Enyedi, Hungary-Germany-France-Italy 2021) are divided into “chapters”, each with a title, as if the director's intention were to signal to viewers that, as in a book, a story is being told, and that a well-defined sequence of events is therefore to be expected. |

|

|

La La Land (Damien Chazelle, USA 2016) makes rather explicit references to classical Hollywood musicals from the 1930s, such as Shall We Dance (Mark Sandrich, USA 1937): compare the scene in the park with Ryan Gosling and Emma Stone with the one (at 1:10:25), also in a park, with Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. This type of reference is obviously only noticed (and appreciated) by the most “cinephile” viewers, and the director's intention will therefore only be partially understood. |

|

|

4. The ‘game’ between director and audience This invitation to recognise the director's presence behind the images, to pay attention to the "signals" or “clues” that the director, more or less consciously, has scattered throughout the film, thus leads viewers to speculate on what mental states led the director to make the choices he made, what he wanted his audience to understand and feel, and by what means, i.e. through what use of cinematic language, he succeeded (or failed) in his intent. Of course, not all the “clues” or “signals” left by the director are equally visible: some may be more explicit and point us towards fairly clear interpretations, while others may be more implicit and suggest meanings in a more indirect way. The director may have deliberately left these clues, but he may also have done so unconsciously, or he may not have been able to hide them ... This implies that viewers can be involved in “decoding” these signals at different levels of awareness, from simple feelings or impressions to more thoughtful reflection, to critical analysis that subjects the film to a more detailed and in-depth examination. And, as we have repeatedly emphasised, individual differences are crucial in this case too: depending on one's prior knowledge and experience, the situation, mood, and the “commitment” with which each person approaches the cinematic experience, each viewer “works” at different levels (of awareness, depth, analysis, etc.) and thus arrives at personal hypotheses about the director's intentions in making a certain film in a certain way. This process, by which viewers attribute particular intentions to the director, is neither automatic nor mechanical: on the contrary, just as we have emphasised the differences between viewers, we must also remember that directors differ from one another, both in terms of their own level of awareness and in terms of their (implicit or explicit) desire to stimulate their viewers to reflect on their films in some way. In short, the real intentions of directors, which are not always clearly expressed, should not be confused with the hypotheses made by viewers - and perhaps it is precisely in this continuous and inevitable “game” between director and audience that lies one of the most intriguing aspects of cinema as a rich and complex form of communication. 5. The different choices made by directors “There are two types of directors: those who take the audience into account when conceiving and then making their films, and those who do not. For the former, cinema is a performing art; for the latter, it is an individual adventure.” François Truffaut (Note 1) Truffaut summarises the differences between directors in terms of their relationship with the audience, i.e. the viewers. A director may decide to cater as much as possible to what he believes to be the tastes of his/her target audience, meeting their expectations and creating a work that minimises ambiguity in interpretation. To do this, he uses clear and transparent cinematic language that conveys the meanings (and emotions) associated with the story and characters in a fluid and coherent manner. One way to achieve this is to adhere more or less radically to a film genre: the director will then use the “typical” forms and content of, for example, a western or a horror film, to allow viewers to make full use of their previous knowledge and experience of this genre of film. At the opposite extreme, a director of “experimental” films does not set out primarily to be “understandable”, let alone to necessarily “appeal” to all his/her potential viewers: the concern to engage with the audience is secondary to the desire to create something new and unexpected, thus making the making of a film, first and foremost, an “individual adventure” (as Truffaut says) rather than a socially shared action. Of course, between these two extremes there are all kinds of intermediate situations, i.e. directors who try to balance the demands (especially commercial ones) of “entertainment” on the one hand, and their own aesthetic and cultural ambitions on the other - and this can also lead to the creation of films that seem to present both of these positions. Truffaut, who had such a clear distinction between these two types of filmmaking, undoubtedly considered Hitchcock to be a director who was very attentive to the needs and desires of the audience, but, as we have seen in the case of Vertigo, Hitchcock himself liked to include elements in his films that not all of his viewers would appreciate, let alone perceive or understand. In this sense, Hitchcock, as well as being a very popular director, was also an “auteur”, in the sense that Truffaut and all his colleagues of the French nouvelle vague of the 1960s understood as the figure of the director, i.e. an artist with almost total control over his work, thus able to leave his unmistakable mark on it, regardless of recognition and appreciation by the audience. Every director, therefore, can decide to make his intentions and choices more or less transparent and understandable to all or some of his potential viewers, reserving the right, if he wishes, to include elements that have meaning and emotional resonance only for himself (and which will not necessarily be made known or explained to the audience). It may also be the case that these elements are chosen without full awareness: as a matter of fact, directors constantly draw on their personal experiences, conscious and unconscious, to make their film, just as every viewer uses what we often call their personal “baggage” of knowledge and experience to understand, interpret and ultimately appreciate (or not) that same film. As Miguel Gomes, director of Tabou, once said: “I make all these choices on set, not before. But I understand them when I watch the film, not during filming. A little more during editing, but not in such a rational way. I just have a feeling that it's right, that it's good.” (Note 2) This reconfirms the subjective nature of a director's choices and intentions, who, even when communicating with viewers through his/her film, can decide, with greater or lesser awareness, to make aspects and elements of the film understandable and appreciable by everyone, by some, and even, in a “gratuitous” way, by no one in particular. This also reconfirms that the personal “baggage” of the director and that of each of his/her viewers can be shared, but gradually, on a continuum ranging from universal values that everyone potentially shares to the most personal idiosyncrasies. If, on the one hand, one could expect a director wanting his/her film to be understood thanks to knowledge and experiences shared by everyone or by many, on the other hand, one cannot limit free creative expression that does without this knowledge and experience. It would also be desirable for viewers to acquire as much knowledge and experience as possible, as this would greatly increase their ability to understand and appreciate each film and more diverse films - perhaps giving them the opportunity to discover that a certain film is a “good” film ... 6. The different “languages” spoken by cinema Closely related to this discussion is the question of the “languages” that directors use in their work. We have seen that some of the elements or aspects of a film that are sometimes less “transparent” and more difficult (or less easy) to understand are visual in nature: the motif of the “spiral”, which recurs several times in Vertigo, from the swirls in the opening credits to the woman's hairstyle, from the spiral staircases to the protagonist's vertigo, despite being explicitly staged several times, may not be grasped by viewers, at least not in the same way that they understand a dialogue between characters or a very familiar image or sound. This refers to the very nature of cinema, which is a multimedia tool that uses languages that are very different from each other: from the verbal to the visual and auditory, with a complex interrelation between the languages themselves provided by the staging, from what is directly visible ("on-screen") to what remains invisible even if presupposed (the "off-screen"), from the camera movements to the editing, from the use of special effects to the soundtrack. Not all of these "languages" are immediately understandable and interpretable by the audience: in particular, verbal language, which tends to clearly define its contents, is only part of the experience provided by a film, which offers a much broader and more nuanced range of messages. Just as it is sometimes difficult, if not impossible, to translate an entire film into a purely verbal description, even more difficult is using this same language to describe the intentions of the director we feel we have grasped while watching one of his films. The limitations of verbal language, which tends to be analytical, explicit, even "digital," are immediately evident when faced with the images and sounds conveyed by a film, which are often global, implicit, "analog," and which often refer not to individual, well-identified elements but to experiences, memories, knowledge, in the viewer's mind. Watching a film is an "experiential" fact, involving, far beyond the sensory channels of simple "sight" and simple "hearing," our deepest cognitive, affective, and motor mechanisms, our memory, our entire body being stimulated in all its richness and complexity. And it is precisely thanks to this complex experiential language, closely linked to the reality we experience as well as to the reality that the film offers, that we are able to understand, interpret, and appreciate elements of a film that the use of verbal language alone would fail to capture. Certainly all this takes on greater relevance in the face of those films which, as we have already discussed, include the result of directorial choices that are less immediately understandable by the audience, or which at least lend themselves to more than a single interpetation. Picnic at Hanging Rock, for example, could at first be considered simply (or just) a thriller: it tells the story of an excursion to a desert site by some girls from a girls' school in early twentieth-century Australia, during which some of them climb rocks, completely disappearing. As a thriller the film "works", although the mystery of this adventure is not revealed at all (which some viewers would consider a serious flaw for this film genre). But watching the film goes far beyond the events surrounding the story, which are all in all rather sparse, and even the least warned viewer notices that the numerous images of nature and the relationship the girls seem to have with these fascinating yet disturbing places seem to "mean" much more - or, in other words, that the director's intentions go well beyond simply telling the story of a disappearance. But, if this "story" can also be described analytically with verbal language, an effort is required to be able to identify the message conveyed by the richness and ambiguity of the images (which are also closely integrated with the "story" itself). We understand that these images call into question our sensory experience, both as human beings and as spectators - we are invited to make sense of what we see, but also to understand the emotions we contextually perceive. |

|

|

Picnic at Hanging Rock (Peter Weir, Australia 1975) The images of the girls climbing to the top of the rock alternate with images of the landscape, both fascinating and menacing. The director's insistence on this sometimes even anthropomorphic nature insinuates a sense of mystery but also of almost metaphysical "horror". As spectators, we perceive these subtle sensations of attraction towards something unknown, as attractive as it is disturbing... |

|

|

At one point the girls lie down in a clearing and fall asleep. Nature imposes itself again, with the image of a small snake crawling alongside the girls' bodies. The image of the teacher, looking up, towards the top of the rock (at 00:39), is immediately juxtaposed with the image of a geometry text: what is the function of this sudden juxtaposition? The governess seems to interpret her vision of the rock with the use of a scientific image ... while immediately afterwards three of the four girls, on waking up, resume the climb, almost "in a trance". The fourth girl, frightened, comes down and her terrified scream fills the silence of the place. A more warned viewer will be able to sense that the director wanted to represent a theme dear to him (and which he will take up, at different levels, in his subsequent films): "the unsolvable conflict between culture (rational, prissy, oppressive) and nature (irrational, vitalistic, liberating)" (Note 3) |

|

|

A film like Picnic at Hangin Rock therefore lends itself to

many "interpretative paths" and at the same time raises many questions,

at different levels of complexity. If it's a thriller, why aren't we

given the solution to the intrigue? What's the function of the (almost

obsessively exhibited) images of nature? Are they just a way to show us

beautiful natural views? But in this case, why are they so numerous and

incisive? Does the choice to set the film in early twentieth-century

Australia, in a period still marked by colonialism, have any particular

significance? And, if we know the director's subsequent films, such as

Dead Poets Society (a melodrama about a charismatic teacher and

his students) or Green Card (a "romantic" comedy with a happy

ending), how can we interpret Picnic at Hanging Rock in light

of the recurring motifs in his filmography? All legitimate questions,

which not all viewers naturally ask, but which give an idea of the many

ways in which a film can be "interrogated" and the many possible answers

-answers that perhaps constitute just as many good reasons to judge a

film as a "good" film ... 7. Between analogies and metaphors The languages that cinema uses, not only to narrate stories and describe characters and environments, but also to suggest meanings and stimulate emotions, can therefore pass through the more or less sophisticated treatment of images and sounds, which by their very nature are evocative, that is, they can bring out in spectators diversified ideas and states of mind, depending on the predispositions and attitudes, as well as the knowledge and experiences, with which viewers themselves approach the cinematic experience. In this way the director's intentions are continuously reinterpreted, provided with meaning and value. However, the use of cinematic languages can be more or less direct/indirect and more or less implicit/explicit, which entails a different commitment to perception and interpretation on the part of viewers. The use of analogies, for example, through which some images can suggest memory and comparison with other images stored in our minds, can be more or less easy, depending on the immediacy of the images and, of course, the knowledge that the viewer must activate. (Post) modern cinema often uses more or less explicit references to other films: for example, Quentin Tarantino's cinema is filled with "memories" of films, which the director (an inveterate cinephile) reuses and in a certain sense "recreates", often with satirical intent: a "war" film like Inglorious basterds or a "revisionist" western film like the already mentioned Django Unchained contain a variety of elements (especially formal and stylistic) that refer to Italian films from the 60s and 70s belonging to the same cinematic genres. It is certainly not essential to be aware of these "references" to appreciate Tarantino's films, but the more astute viewer will certainly have an extra chance to enjoy them. |

|

|

Inglorious basterds (Quentin Tarantino, USA-Germany 2009) |

|

|

The use of metaphors, through which two scenes are related to

each other to stimulate comparison and thus enrich their understanding

and interpretation, can also be more or less direct and explicit. If the

two scenes are juxtaposed through editing, the effect can be captured

quite easily even by viewers who are not particularly sensitive and

warned. When Fritz Lang in Fury juxtaposes the image of a group

of women with that of a chicken coop, the weight of gossip and chatter

is immediately underlined; and when Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times

juxtaposes the image of workers leaving the factory with that of a flock

of sheep, the message of alienation and passivity to which the workers

themselves are reduced is evident (especially if these images are

related to the sarcastic caption that precedes them: "'Modern

times.' A story of industry, of individual enterprise - humanity crusading

in the pursuit of happiness." |

|

|

Fury (Fritz Lang, USA 1936) |

Modern times (Charlie Chaplin, USA 1936) |

|

This is a procedure that is not without possible criticism (for example,

for those who believe that in this way the director's "hand" is all too

evident, or that the "realism" of the scenes is endangered), but which

even in more recent times directors/authors such as Woody Allen have not

hesitated to use: in Crimes and Misdemeanors, the image of the

protagonist's rival is compared to images of Mussolini and a donkey ... |

|

|

Crimes and Misdemeanors (Woody Allen, USA 1989) |

|

|

At other times the metaphor can be more subtle and involve not a single

scene or sequence but an entire film. The artist, for example,

tells the story of two Hollywood stars at a crucial moment in cinema,

the transition from silent to sound in the late 1920s. But the film

achieves this "reenactment" in a radical yet surprising way: the film is

itself silent and respects to the letter all the conventions typical of

those first decades of cinematic history: it is shot in a "square"

format, in black and white and with intertitles inserted to explain the

dialogues. The story focuses heavily (as it did, in a completely

different vein, Singin' in the Rain) on the transition, for

many dramatic actors, between silent and sound, with the protagonist

stubbornly wanting to produce a silent film when this type of cinema is

now running out of steam, and, on the contrary, the dancer at the

beginning of her career and therefore projected towards the future. But

the director does not focus so much on events and characters as on the

portrait of a particular setting, described with nostalgia and

affection. And viewers are drawn into this operation, which can be read

as a metaphor for the decline of a world that also evokes emotions of

nostalgia and almost regret: as if nostalgia for a distant past

corresponded with the nostalgia that all of us (or at least, many of us)

have felt in at least partially similar situations. An on-screen past,

then, that speaks to the audience's present. And the director seems to

be playing with the challenges that such a film project continually

poses to him, in an attempt to be able to shoot, in 2011, a film without

words. Once again, the director's intentions (and emotions) can thus be

mirrored in those of his viewers, called upon to share this adventure

with him - and the experience of this film (for both director

and audience) transcends the story told to take on a more universal

value. As Pignocchi wrote, albeit about another film (the aforementioned

Tabou) (Note 4): "The question is not about the director artificially imposing technical limitations on himself, but about recreating some of the sensations that silent films can provide to today's viewers. First, they can prompt reflection on the virtues of economics: without dialogue, all our attention faculties focus on facial expressions, glances, and all those bodily elements that, more than words, are linked to emotions ... In a silent film, we are more receptive to the way the music dialogues with the story, and when the sound adheres precisely to the image, we almost have the impression of a miracle ..." |

|

|

The artist (Michel Hazanavicius, France 2011) |

|

|

8. Conclusion: Does analysis prevent "immersion" in a "good"

film? Some might argue that reflecting on a film, or analyzing it in less or more detail, ends up damaging our immersion in the story told and the characters' experiences, jeopardizing our emotional involvement and ultimately affecting our appreciation and final judgment of the film. In reality, one could respond to this objection by stating that analysis and immersion are not two such separate and almost conflicting procedures. We have seen that becoming more aware of aspects and elements of a film that may not be so obvious at first glance can make our viewing experience richer, and in fact more engaging. Analysis and reflection can then serve to make the reasons for our interest and involvement more explicit and understandable - and this not only during viewing but also after viewing, when perhaps we happen to or decide to rewatch all or part of a film. Finally, critical reflection, or, more simply, becoming more aware of aspects, elements, or motifs of a film, can take various forms and be conducted at various levels of detail and depth. Not everyone can or will want to conduct a critical analysis, but everyone may, depending also on the contexts and situations in which we watch a film, be led to ask questions about what the film (and its director) intend to make us understand and feel, and also, sometimes, to ask how the director managed to prompt these same questions, by what means and through which specific uses of cinematic language. Ultimately, not everyone will want to make the effort to reflect on a film, but everyone should be allowed the freedom to do so. The concept of a "good movie" remains elusive, but if the impossible question "What is a good movie?" cannot lead to an absolute answer, we can still ask ourselves what drives us to judge a film the way we do ... thereby reaffirming the right of every spectator to his/her own taste and to derive his/her own personal pleasure from a film. |

|

Note

1. Truffaut F. 1975. Les films de ma vie, Flammarion, p. 104. Quoted in Pignocchi A. 2015. Pourquoi aime-t-on un film? Quand les sciences cognitives discutent des gouts et des couleurs, Odile Jacob, Paris, p. 191.

2. Quoted in Pignocchi, op. cit., p. 263.

3. Il Mereghetti, Dizionario dei film. Baldini e Castoldi, Milano.

4. Quoted in Pignocchi, op. cit., p. 294.